The Life of Salim C. Wilson (Hatashil Masha Kathish)

Archie Wood, University of Sheffield Graduate and Dynamic Collections Project Volunteer

Early Life and Dinka Heritage

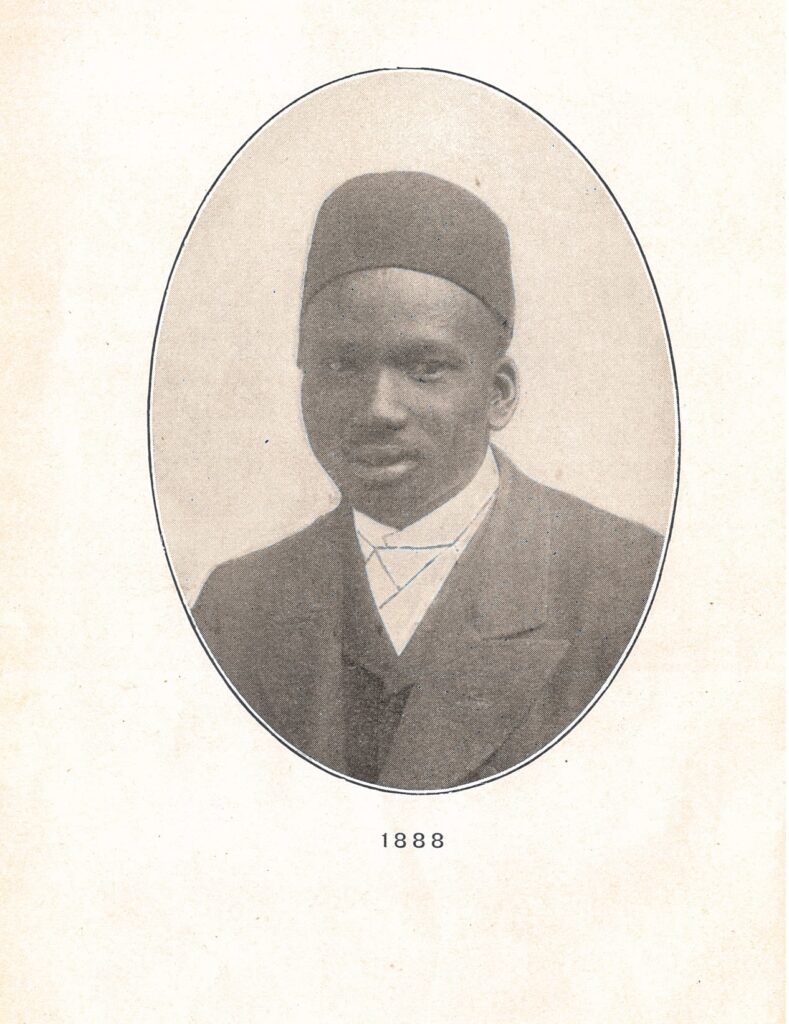

Salim C. Wilson, born Hatashil Masha Kathish around 1860 near Amerwai in South Sudan, was the son of a Dinka tribal chief. The Dinka, a pastoralist tribe, deeply influenced Salim’s upbringing. His name reflected significant aspects of his family history and role in the tribe. Hatashil, meaning the Continuer, referred to his father’s leadership role in the Dinka community. Symbolizing the tribe’s request for him to remain as their chief. Masha, meaning the value of the Black Ox, was tied to an incident during his father’s leadership when he insisted on keeping a prized black ox during a negotiation involving cattle. Salim often attributed this humorous naming to his father’s wit. Finally, Kathish, meaning Asked of God, represented his family’s prayers for a son after having many daughters.

Salim’s life took a traumatic turn when Arab traders first arrived in Dinka territory. Disguised as legitimate traders, these Arabs engaged in dishonest bartering, which escalated into conflict. Over several years, tensions grew. Eventually, the Dinka people were drawn into armed conflict with the Arab slavers. Initially, the Dinka were successful in defending their lands. But the Arabs ultimately overpowered them.

The defeat was devastating. Salim described the aftermath as a time of intense cruelty, recalling that “the happiest were those who had fallen in the fight.” His father was one of the many casualties, fatally shot while trying to protect Salim. This memory haunted Salim for the rest of his life, as he vividly recalled watching his father’s last moments.

Enslavement and Early Hardships

After the defeat, Salim and his people were captured and enslaved by the Arab victors. Salim describes the brutality of his captors, who bound the hands of the enslaved with leather thongs and forced them to carry goods on their journey into slavery. He likened this treatment to being reduced to the status of a “beast of burden”. Yet he remained determined to hold onto his identity, refusing to allow the enslavers to dehumanize him entirely.

His first enslaver, described as comparatively kind, still imposed servitude on the young Salim. The slaver renamed him Salim, which is an Arabic name meaning safe. Salim would go on to use both names, Salim and Hatahsil Matha Kathish, throughout his life. His duties included fetching water, preparing coffee, and laying out his master’s prayer mat. Despite the harshness of his situation, Salim noted that he was not starved, unlike another Dinka boy who suffered greatly under his own master. However, the psychological impact of slavery was evident, as Salim recalled being forced to perform and sing for guests. A sad or dejected appearance during these performances could result in severe punishment, including beatings.

Salim’s situation deteriorated when his first enslaver facing financial difficulties, sold him to a new, more brutal master. Under this new master, Salim was subjected to extreme abuse. He was forced to fight older boys for entertainment. One instance of severe punishment left a permanent mark on him. After accidentally allowing gun cartridges to become wet, Salim was beaten so severely that his master believed he had killed him. This incident left Salim with a deep scar, both physically and emotionally. His master cut three gashes into each of Salim’s cheeks and rubbed a mixture of gunpowder and salt into the wounds, a traditional method intended to leave permanent marks. Salim later remarked, “The anguish of that hour will remain with me as long as I retain any memory.”

Despite these hardships, Salim retained a fierce desire for freedom. He often considered escaping but was acutely aware of the dangers. He had seen what happened to others who attempted to flee – they were often captured and tortured or killed. The constant threat of retribution kept him from acting on his desire to run, as he felt trapped with no knowledge of where to go.

Liberation and Religous Awakening

Salim’s path to freedom came unexpectedly when Lieutenant Colonel Romolo Gessi’s soldiers, part of General Charles Gordon’s anti-slavery campaign in the Sudan, liberated him. The campaign aimed to combat Mahdist forces and abolish slavery in the region. Though freed from physical bondage, Salim, like many former slaves, faced the reality of having no home to return to. His village had been destroyed. His family scattered, and his father was dead. With nowhere to go, Salim sought refuge with the soldiers, joining their camp.

It was during this period that Salim’s life took a new direction. While traveling with the army, he encountered Reverend Charles T. Wilson and Dr. R. W. Felkin, missionaries who were passing through the region. Despite his initial fears about traveling with the Europeans, Salim volunteered to accompany them back to England.

Salim’s arrival in England was a bewildering and awe-inspiring experience. He was exposed to a world vastly different from the one he had known, filled with strange sounds, sights, and customs. He was determined to learn English and absorb as much knowledge as possible. During his time in Pavenham, where he attended school, he developed a fascination with Christianity. His desire to understand Christian teachings led him to immerse himself in the Bible, seeking answers to questions about Heaven and salvation. On 28 August 1882, Salim was baptized at Holy Trinity Church in Nottingham by his benefactor, Reverend Wilson. This ceremony marked a major milestone in his spiritual journey. Salim embraced his new Christian identity with fervour.

Training and Missionary Work

Salim’s commitment to his faith deepened when he enrolled at Hume Cliff College in Derbyshire, a prestigious Missionary Training Institute. He dedicated himself to studying Christian theology and learning Bible passages, preparing for a life of preaching and spreading the Gospel. During this time, he gave his first public sermon in Burton-on-Trent, where he spoke to an audience of over 700 people. The experience solidified his calling to serve as a preacher.

After completing his studies, Salim’s missionary work took him to Palestine with Reverend Wilson. This journey was significant, as it allowed Salim to visit important religious sites such as Jerusalem and Bethlehem. He also had the opportunity to meet General Gordon, the man who had led the troops responsible for his liberation. This meeting was deeply moving for Salim, who received a sovereign coin as a gift from Gordon. A keepsake he treasured for the rest of his life.

Return to England and Preaching in the North

Upon his return to England, Salim continued his missionary work, focusing on preaching across the north. He settled in Yorkshire, where he obtained a license as a lay reader and began working with various churches. In 1911, he moved to Scunthorpe to join the Bethel Free Mission. Here he quickly gained recognition as “The Black Prince,” a reference to his royal Dinka heritage. His marriage to Eliza Alice Holden in 1913 drew much local attention and was even filmed by a local cinema. Large crowds gathered to witness the union. Despite initial concerns about racial tensions, the wedding was a joyous occasion, and Salim became a beloved figure in the community.

Salim built a life for himself, constructing four terraced houses and opening a small general store in Kathish Villa. His warm, engaging personality made him a cherished figure in the town. Parents would often introduce their children to him, seeing him as a figure of moral authority and kindness.

Legacy and Final Years

Salim’s later years were marked by personal tragedy, as his wife fell ill and eventually passed away in 1941. Salim spent much of his savings on her treatment. But despite his financial hardships, he continued to preach and serve his community. He died on 26 January 1946, and was buried beside his wife in Scunthorpe.

Salim’s legacy extended beyond his death. In 1988, a group of Dinka exiles visited Scunthorpe to honour his memory, recognizing him as a symbol of resilience and cultural exchange. His story serves as a powerful reminder of the ability to overcome adversity, and his contributions to the community of Scunthorpe remain a testament to his enduring spirit.

About the Author

Archie Wood is a history graduate from the University of Sheffield, specialising in the transatlantic slave trade, Indigenous histories, and the lives of underrepresented figures from the 18th to the 20th centuries. With a background in historical research and human rights, Archie seeks to illuminate stories of resilience, transformation, and identity across diverse communities. His work focuses on the intersection of history, identity, and migration, often exploring how individuals and groups have navigated complex socio-political landscapes throughout history.

More to Explore

The Black Evangelist of the North

Poet and performer, Tia Goffe, shares the life of Salim C. Wilson/Hatashil Masha Kathish through verse.

Read the story

Ten Years A Slave, Fifty Years A Preacher

A century after his marriage to a Scunthorpe woman, Salim Charles Wilson’s name is largely unremembered locally. Tim Davies takes a fresh look at an unjustly forgotten celebrity from the early twentieth century.

Read the story

Madam C. J. Walker

Scunthorpe based creative writing student, Tia Goffe, highlights a woman of colour who inspires her.

Read the story

My Inspiration by Zainab Tasneem

Local writer, Zainab Tasneem, highlights a woman who inspires her as a British Pakistani woman.

Read the story