Ten Years A Slave, Fifty Years A Preacher

Tim Davies, Partnerships and Communities Librarian

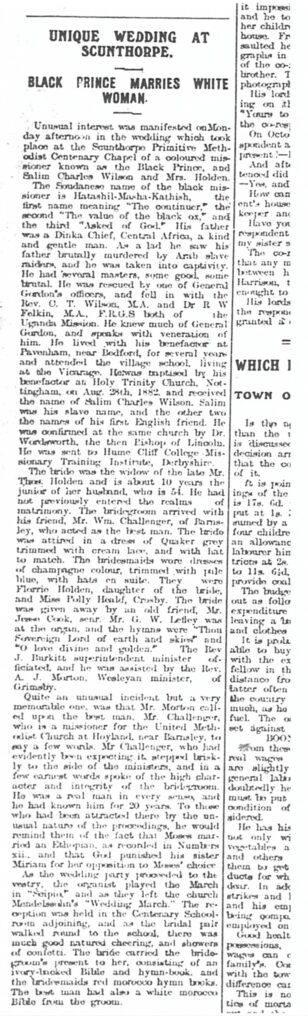

The Scunthorpe & Frodingham Star of 16 April 1938 carried a small inside-page article noting the silver wedding anniversary of a popular and well-respected couple, a Mr and Mrs S. C. Wilson of Frodingham Road. The article recalled that the happy day itself had been something of an event: “Crowds lined the streets outside and around the [Centenary Methodist] Church, and Mr Wilson describes with some amusement the antics of one of the onlookers who swarmed up a lamp-post to get a better view of the couple.”

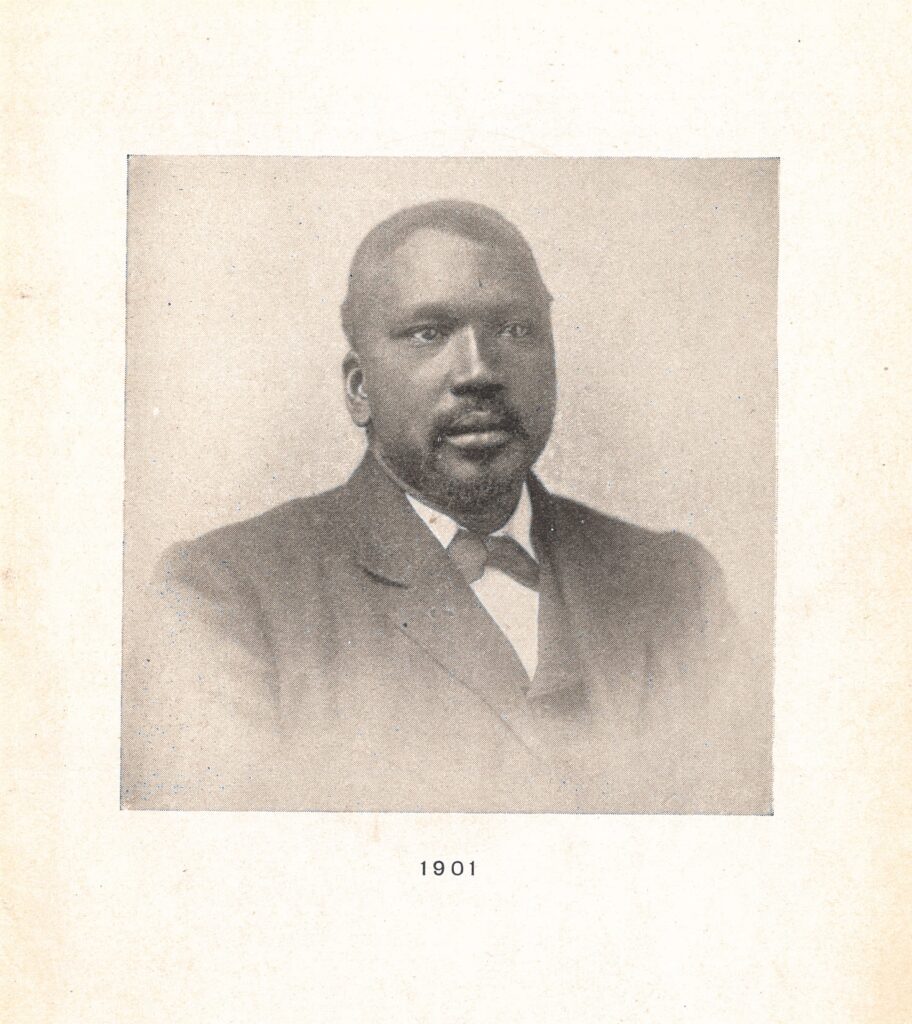

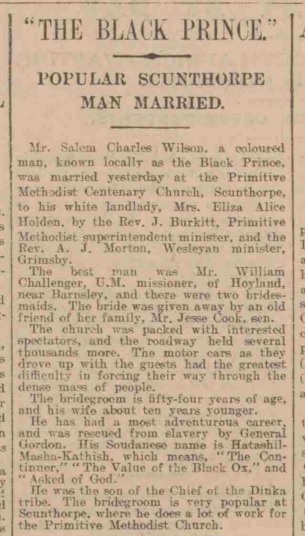

While everyone likes a good wedding, the “extraordinary amount of interest” surrounding this one may have been due to the fact that the future Mrs Wilson, a widow in her early forties, was her bridegroom’s landlady. But it will also certainly have had something to do with the figure Mr Wilson cut. A tall, good-looking man in his early fifties, with an upright, dignified bearing, he had permanent scarring on his cheeks from a painful episode in his youth. Arrived from Barnsley barely two years previously, he had already become a fixture on the local Methodist circuit and was much in demand as a preacher and speaker.

He was also black.

Salim Charles Wilson, or Hatashil Matha Kathish, to give him his original name, was born around 1860, not even he was quite sure of his exact age, in what is now South Sudan. His father was a chieftain in the Dinka tribe, semi-nomadic pastoralists who had an uneasy relationship with their northern Arabic neighbours (a situation which still partly pertains today). When Kathish was in his early teens, an Arab raiding party attacked his settlement, killed his father in front of his eyes, and dragged Kathish himself and others off into slavery.

In fact, the boy’s first master was a benign man, in the circumstances, who treated him kindly. He gave the boy the name Salim, from the Arabic for “safe” and related to the word for “peaceful”, which Kathish continued to use for the rest of his life. This man only sold Salim on when he got into debt. He was exchanged for six yards of calico – valued at 1s 3d in total, about £50 today – and, sadly, the “new Master proved to be a creature who might fitly be called a Demon. To make me wretched was his greatest delight…” (“Jehovah-Nissi: the life story of Hatashil Masha Kathish”, 1902; p.32).

On one occasion, the young Kathish stumbled while crossing a stream and ruined the rifle cartridges he was carrying. His new master beat him so hard that he was left for dead. On being taken by some passing traders to a nearby town, Kathish was recognised and reclaimed by the man. To mark him as his property, the slaver cut three gashes in each of the boy’s cheeks with a razor, rubbing a mixture of gunpowder and salt into the wounds. The scars remained for the rest of Kathish’s long life.

A rebellion by the Arab slavers against the British and Egyptian authorities was supressed by troops under the command of General Charles Gordon, Governor-General of Sudan. Many slaves were freed as a result. Salim/Kathish came to the attention of a member of the Church Missionary Society, Rev. Charles T. Wilson, and so after a little time found himself brought to England.

Charles Wilson’s father was the vicar of Pavenham, Bedfordshire, and Kathish spent a couple of years there receiving an education at the local school. In his autobiography, he recalls:

Generally speaking, the Pavenham lads were kind. At the school to which I was sent, the boys soon found that I was anxious to increase my stock of knowledge, and did their best to help me. One would hold up a thing and give me its name, and I had to repeat it after him. Sometimes I was very wide of the mark, and then, amid roars of laughter, I had to try and try again till the difficulty was conquered. I endeavoured to master the Alphabet at the village school, but I am afraid the strange noises I made, as I grappled with letter after letter, little tended to the quiet of the school…

(“Jehovah-Nissi”, p.48)

With his dark skin, permanently scarred cheeks, ill health through years of neglect, his illiteracy and his ignorance of British society and Christianity, Kathish must have been a curious novelty to his fellow pupils. He would also have been rather older than them, being around twenty by this time. It suggests considerable strength of character that he was able to set aside his traumatic early life and get himself quickly welcomed and accepted, besides having the grace to look back on the confusing early days of his life in England with self-deprecating humour.

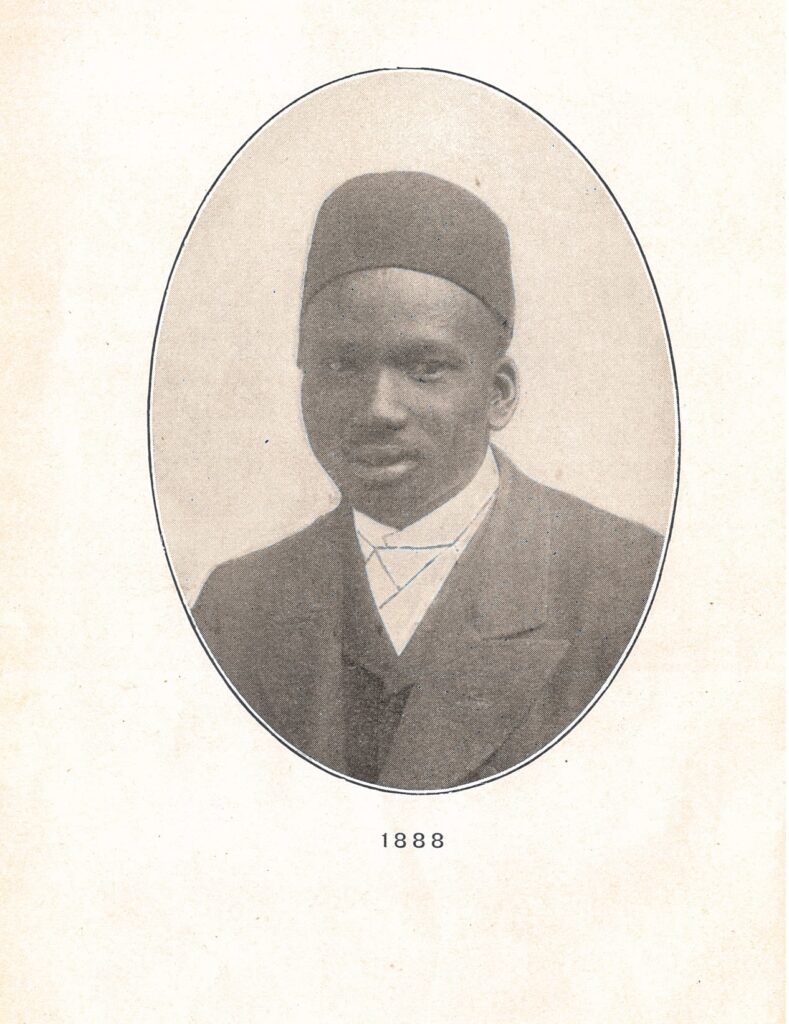

He was obviously a quick leaner. In August 1882, barely two years after his arrival, he was baptised at Nottingham and took the name Salim Charles Wilson out of respect for his benefactor. He was sent to study at Hulme Cliff College, now Cliff College, an evangelical missionary training institution in Derbyshire, where he increased in confidence and in faith. His studies were interrupted by being invited to accompany Charles Wilson on a trip to the Holy Land. But he eventually returned to Hulme Cliff, leaving there in 1886.

While he was still a student, tensions between the Sudanese Arabs and the British and Egyptian authorities in Salim Wilson’s homeland came to a head. The ensuing conflict was brutal on both sides and culminated in the annihilation of Gordon and his troops at the Siege of Khartoum. The Superintendent of Hulme Cliff began taking Wilson out on speaking tours around the North of England:

We visited a number of the chief towns, and held very large meetings. I appeared on the platform in a leopard skin after the fashion of a Dinka Chief, and was thus made to remember my old name Hatashil, or “The Continuer”.

(“Jehovah-Nissi”, p.57)

The purpose of the tour seems to have been to raise awareness of Sudan and the perceived need to evangelise it, and to foster abolitionist feeling by reminding audiences that slavery still existed in parts of the world. In 1887, Wilson made an abortive attempt to return to Sudan and bring his own people to Christ. Although to do so remained a dear wish of his, the circumstances never again aligned. He was obliged to focus his preaching career on his adopted homeland instead. For 25 years, he toured the country from his base in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Then in 1911 he moved to Scunthorpe to help with the Bethel Mission here.

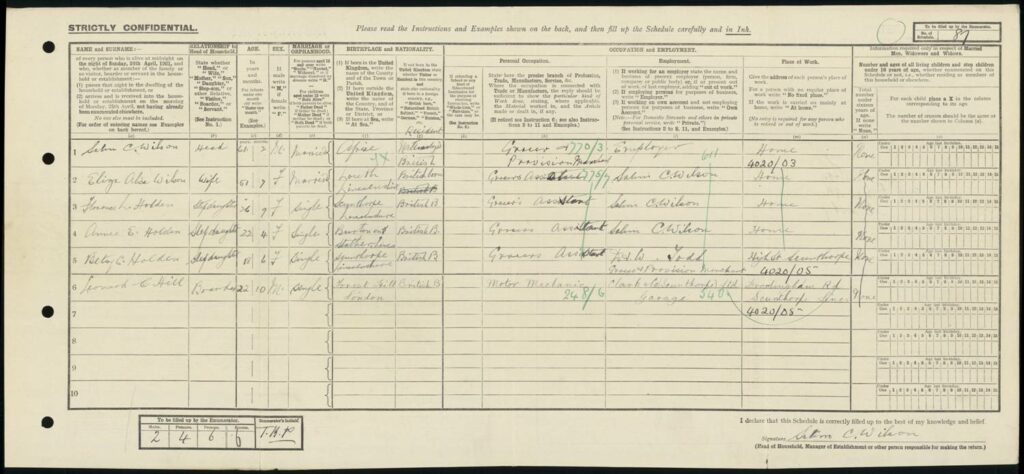

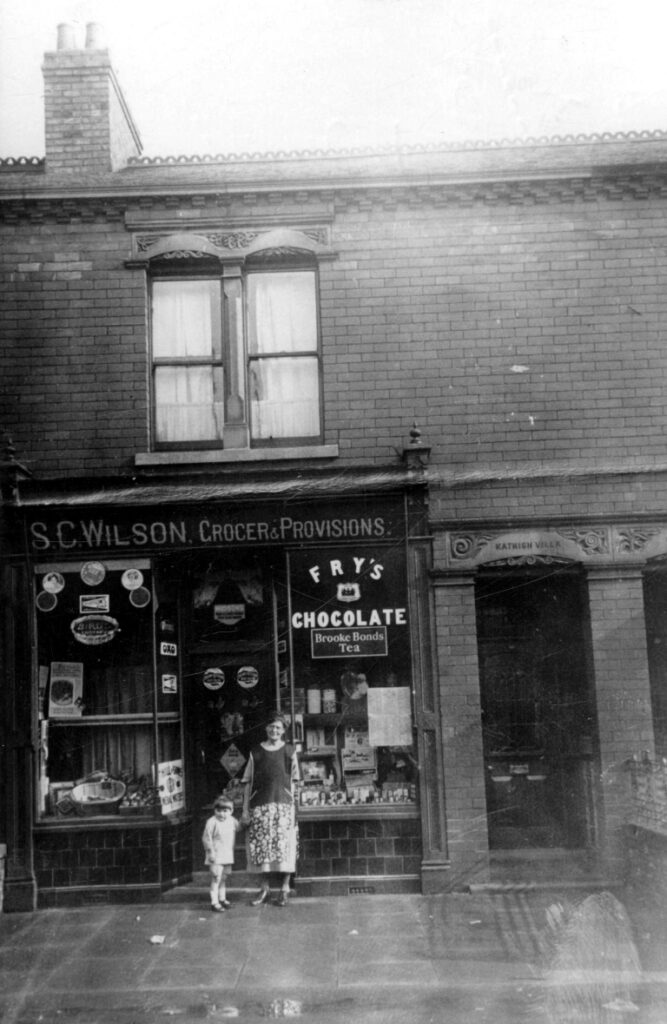

Wilson quickly established himself in North Lincolnshire society. He was a regular preacher at both the Centenary Methodist Church and the Diana Street chapel, as well as visiting many others. Although he remained a preacher and abolitionist speaker, he and his wife also built up a successful grocery business at the top of Frodingham Road, round the corner from Mrs Wilson’s house on Burke Street. In his article “Salim Wilson: the black evangelist of the North” (‘Journal of Religion in Africa’, vol.21/1 (Feb 1991) pp.26-41), Douglas Johnson quotes several Scunthorpe people who remember Wilson from their childhoods with respect and affection. He became comfortable enough to build a small terrace on Frodingham Road, naming one house “Kathish Villa” and another “Gordon Villa”; the buildings are still there today.

Much of the couple’s money eventually went on caring for Mrs Wilson in her long last illness, and after her death in 1941 Wilson was increasingly unable to look after himself either financially or physically (he would have been into his eighties, and was apparently going blind). He died in early 1946 in the charity hospital in Brigg, on the site of what had been the Workhouse. He and his wife are buried together in Crosby Cemetery.

After his death, the local papers invariably included – alongside highlights of his long life and career – an account of his 1913 marriage to Eliza Holden; they recalled the “lamentable signs of hostility from some of the local population” (Scunthorpe Evening Telegraph, 31 January 1946, p.3). However, in the reports immediately following the day itself – and in the one with which we started, on the occasion of the Wilsons’ 25th anniversary – the crowd outside the church was described as curious rather than hostile, with “much good natured cheering, and showers of confetti” greeting the couple (Scunthorpe & Frodingham Star, 19 April 1913, p.8).

In celebrating his life and legacy nowadays, we inevitably have to deal with outdated language and attitudes. He was known even before his arrival in Scunthorpe as “The Black Prince”. We should note that Wilson’s identity, including his self-identification, as a former slave begins at an early point in his career and never leaves him. That said, most newspaper reports of his speaking engagements stress that he preached the Gospel with as much force and conviction as he displayed in discussing abolition and slavery. While we might also nowadays view as unfortunate the willingness to have him appear in “authentic” dress, we ought to remember that he himself was apparently very proud of his leopard-skin outfit, seeing it as a reminder that he was continuing his father’s legacy as chieftain, even if most of the tribe had been slaughtered or dispersed.

The role of a Dinka chief, Kathish tells us in chapter four of “Jehovah-Nissi”, is a priestly as well as a political one. Their native, pre-colonial religion was based around an abstract supreme being, making it theologically not dissimilar to monotheistic faiths like Christianity. It is suggestive that this son of a chief, who had lost his native people and inheritance, should take to Christianity so fervently and shoulder the mantle of a moral and religious leader in his adopted homeland.

Salim Wilson was without doubt one of the first people of colour to call Scunthorpe home, and it again says much for his considerable abilities, his fierce sense of duty, the life-affirming and generous spirit he by all accounts displayed, and his enormous personal charm – as well as an inherent tolerance in the people of this area – that he was welcomed so wholeheartedly into local society. One hundred and ten years after a curious crowd gathered to cheer and throw confetti as he married his landlady, he remains a local hero whom we can and should be proud to honour and remember.