A Book-larnt Linkisheere Lass

Tim Davies, Partnerships and Community Librarian

Mabel Peacock (1856-1920) is often introduced as her father’s daughter (Edward, the “noted antiquary” of Bottesford) – and so she was – but it does her better service to celebrate her character and achievements for themselves. Not only a dutiful daughter, she was an indefatigable researcher, an accomplished author and, of course, a person in her own right.

The Daughter

Born at Bottesford Manor, the second of three girls and four boys, to Edward and Lucy Peacock, Mabel “spent nearly all the years of my life there till I was thirty-six”(1.), thereafter the family rented out the manor and downsized to Kirton Lindsey.

After Lucy’s death in 1887 (when Mabel was 31) we must assume that Mabel and her older sister Florence acted as both companions and housekeepers for Edward – neither woman ever married or left home. Edward didn’t enjoy the ancestral occupation of farming, preferring to make a name for himself in historical and dialectological research, and although it’s clear he was a much better historian than husbandman, the eccentric demands this placed on his household meant he could apparently be quite hard work. One constant worry must have been the cost of Edward’s obsessions, which burnt through a significant chunk of the family’s wealth. After Edward died in 1915, Mabel worked hard to restore some of the lost financial capital, leaving the estate in a reasonably healthy condition at her own death barely five years later.

The Researcher

Mabel is perhaps best known for co-editing the Lincolnshire volume of the Folklore Society’s ‘County Folklore’ series with Eliza Gutch (published 1908). They were explicit about using written sources for their material – unlike Ethel Rudkin a generation later, who spent years in the field recording oral tradition directly. Nonetheless, the preparation of the volume must have taken a great deal of work, and indeed we know that Mabel had been collecting folklore for many years. Numerous contributions to the Folklore Society’s journal testify to this; that Edward and Florence were also both regular contributors suggests a lively atmosphere of collaborative research in the Peacock household, over a period of some forty years, dating from the girls’ return from an Edinburgh boarding school through to Florence’s death in 1900 and beyond.

Mabel also contributed to the work of the Index and English Dialect Societies, the monumental English Dialect Dictionary, and an 1891 collection of historical essays, “Bygone Lincolnshire”; she wrote regularly to local newspapers, and special-interest publications like ‘Lincolnshire Notes & Queries’, on matters of dialect, folklore and local historical curiosity. Dialect was an abiding interest of both Edward and Mabel as well as her brothers, Adrian and Max: one Peacock glossary of local terms was published by the English Dialect Society in 1877 and another, exhaustive, one was planned by the three siblings. Although this never appeared fully, Mabel continued collecting and organising material for it up until her death, long after the boys had either died or lost interest.

We should also note that by the 1890s her intellectual reputation was high enough for Oxford University Press to commission from her a two-volume edition of the works of John Bunyan.

The Author

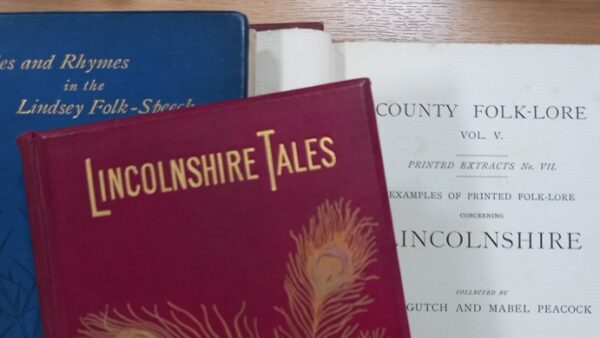

Between 1886 and 1897, Mabel published three volumes of short stories and poems, entirely or substantially in Lincolnshire dialect; a volume of poems in Standard English followed in 1907. The first two of the dialect books, ‘Tales & Rhymes in the Lindsey Folk-speech’ (1886) and ‘Taales Fra’ Linkisheere’ (1889), are miscellanies of folktale retellings, original stories, local riddles and short poems, and a selection of Aesop’s Fables recast into a “Linkisheere” setting. The third volume, ‘Lincolnshire Tales: the recollections of Eli Twigg’ (1897) is a collection of original stories all recounted by the same narrator, telling of life in a fictionalised version of mid-Victorian North Lincolnshire. All the tales are diverse in theme, witty and well-constructed; they are also touching and humane, and full of obvious affection for the varied cast of characters which populate them. The lively dialogue makes plain that Mabel had an extremely sharp ear for natural speech generally, and local speech in particular.

Throughout her adult life, her poems (both dialect and Standard English) appeared in various periodicals and newspapers. One such was a translation of ‘Chant d’Automne’ by modern French poetry’s favourite bad boy, Paul Verlaine (2.). It seems that she was fluent in both French and German, at least as a reader. As an aside, Verlaine spent some time teaching in Lincolnshire in the 1870s, and while it’s tempting to imagine Mabel met him, there is no evidence of this.

The Person

Mabel’s few surviving letters suggest she was concerned for the future of Britain’s rapidly-industrialising society (and nostalgic for a self-sufficient, rural way of life); was a believer in practical education (she regretted that her own schooling had not equipped her to run a household); and had a deep compassion for the plight of the working classes in what felt like uncertain times – she sees the merits of a more socialist society, although is rather jaded about formal politics in general.

The assured handling of speech in her stories – as well as notes in her papers, comments by Edward, and other circumstantial evidence – raises the intriguing possibility that she (and the Peacock family generally) were fluent, if not native, dialect speakers; may we suppose that Mabel conducted household business with her servants in dialect?

Her nephew is noted as recalling that she had a dry sense of humour, but didn’t suffer fools gladly (a general attitude which comes through strongly in her tales); he also notes that she wasn’t too sorry when Edward’s beloved but ancient cat finally died, though we don’t know whether she was generally not a cat person or just took against that particular animal.

It is of course dangerous to assume we can know someone else, especially at some 150 years’ remove when all we have to go on is others’ scanty written accounts and the products of her own pen. However, it is clear that she was a highly intelligent, well-read, careful researcher; a competent poet and excellent storyteller; and entertaining and sympathetic (if perhaps sometimes irritable) company. She’d certainly make a good fantasy dinner party guest…

(1.) Peacock Word Slip: “Bottesford”, North Lincolnshire Museum

(2.) Pall Mall Magazine vol.16, issue 65, p.4 https://archive.org/details/sim_pall-mall-magazine_1898-09_16_65/page/48/mode/2up

Focus On

The Peacock Family

Discover the Peacocks. A family of distinguished scholars from Bottesford Manor.

Read the story

Ethel Rudkin (1893-1984)

Discover the story of folklorist and historian Ethel Rudkin.

Read the story

Curators Choice – Mabel Peacock’s Playscripts

A closer look at the six playscripts written by local folklorist Mabel Peacock of Bottesford Manor.

Watch the film

Otchins, Ghosts, and a ‘tater For Rheumatism: Mabel Peacock’s Dialect Tales

Guest contributor Tim Davies with an introduction to some of the little-known dialect stories of Mabel Peacock, with a look at the use of folklore and tradition in her writing.

Read the story