Otchins, Ghosts, and a ‘tater For Rheumatism: Mabel Peacock’s Dialect Tales

Tim Davies, Partnerships and Community Librarian

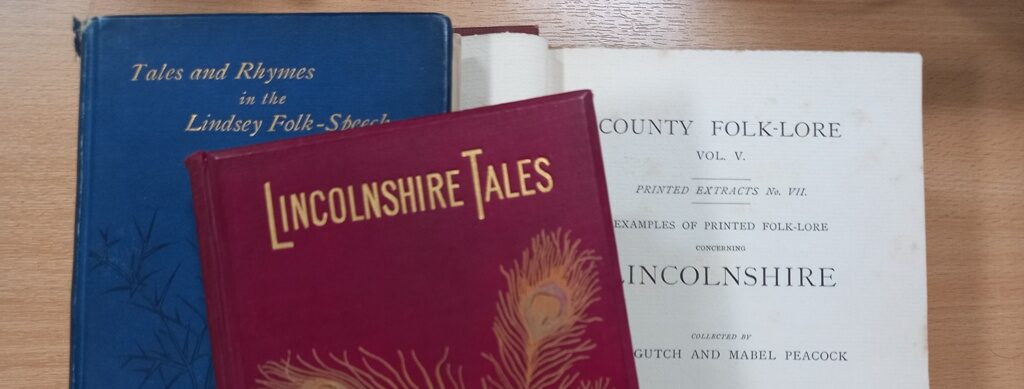

Between 1886 and 1897, the historian and folklorist Mabel Peacock published three volumes of stories and poems in northern Lincolnshire dialect. They are varied, entertaining and surprisingly readable, and this article hopes to give something of their flavour.

Mabel would have been conscious of a long tradition of dialect writing, particularly in northern England, and was working at a time when folklore was the subject of serious study. As the short story was also emerging as a suitable medium for female authors, it’s hardly surprising that a well-read, intellectually active young woman like Mabel should find the combination appealing: “Yorkshire and Lancashire people write in their own words about their own ways, and why should not Lincolnshire folks do so also?” (Tales & Rhymes: Preface).

However, even if dialect fiction wasn’t unknown, and the short story was an increasingly popular form, Mabel was possibly doing something rather unusual. The way her stories reflect her interest in folklore is also unexpected.

Tales, Rhymes and “Folk-Speech”

Tales & Rhymes in the North Lindsey Folk-Speech (1886) and Taales Fra Linkisheere (1889) contain between them nineteen standalone short stories, thirty-eight “owd-fashion’d” riddles, six poems and several retellings of Aesop’s Fables. Of the stories, four are versions of established folktales; the rest seem to be original, although two feel like traditional fables. Apart from one essay in Standard English on Lincolnshire history, in Tales & Rhymes, both these books are entirely in thick dialect.

Lincolnshire Tales: the Recollections of Eli Twigg (1897) is a different book altogether. The title character, a retired horseman in a fictional mid-Victorian North Lincolnshire village, tells his tales to an unidentified listener, who introduces them in Standard English. Eli’s narration, and all the dialogue within each tale, is reproduced in mild but still-credible dialect. The large cast of vivid characters sometimes (re-)appear in each other’s stories, and some later episodes refer to earlier ones. Recollections is clearly a mature and quite sophisticated piece of writing, dealing honestly with the realities of contemporary rural life with an appealing charm and lightness of touch.

All three books were published in limited runs by the Brigg bookseller, George Jackson.

Taters and “Fore-tokenings”

For someone with a lifelong interest in folklore, Mabel includes surprisingly few examples in her tales, although they are always genuine and later referenced in her “County Folklore of Lincolnshire” (Gutch & Peacock (eds.); London, 1908).

One example is the notion that a potato in one’s pocket prevents joint problems. It’s a throwaway comment in a yarn about two quarrelling brothers: by refusing to help when he sees Fred in physical distress, Jesse finds himself accused of murder: “‘Murder?’ says Jesse, ‘and me never within four yards of you, and with nowt but a clean handkercher and a tater for rheumatism on me.’” (Recollections: “Brother and Brother” p.121).

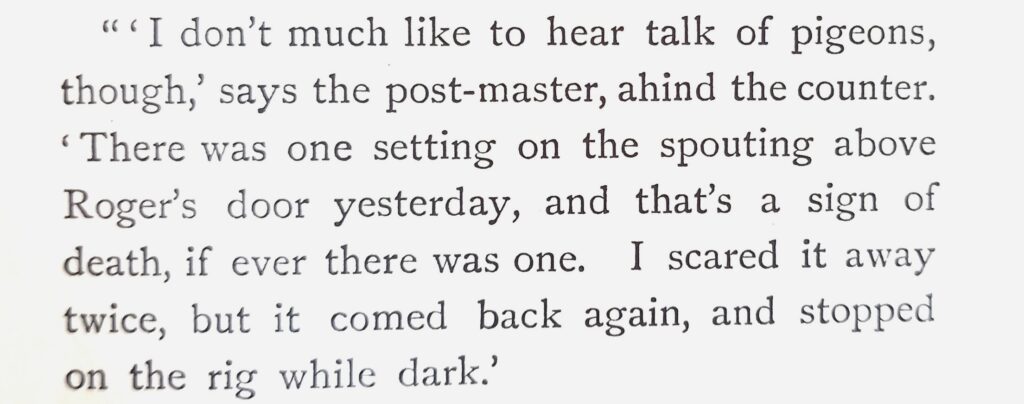

Other instances include believing that a future lover can be identified by certain rituals on St Mark’s Eve (24th April) – in a story about pre-marital pregnancy (Recollections: “Sinning & Saving”, p.49). Or that a pigeon stubbornly returning to a particular gable foretells death in that house – in a story about a fatal accident (Recollections: “His Wedded Wife” p.285).

Ghosts

Pigeons and the folklore of death aside, in one or two instances Mabel affectionately subverts the Victorian craze for the Gothic. Recollections has two fine examples:

In “The Temple-Leys Ghost”, a house is plagued by unexplained groanings and bangings – the maid swears it’s the ghost of a notorious local suicide. Her sceptical master and the parson sit up one night with a bible, the fire poker and bottle of good brandy. A simple (and amusing) explanation is uncovered for the bumps in the night, but not before some hair-raising moments.

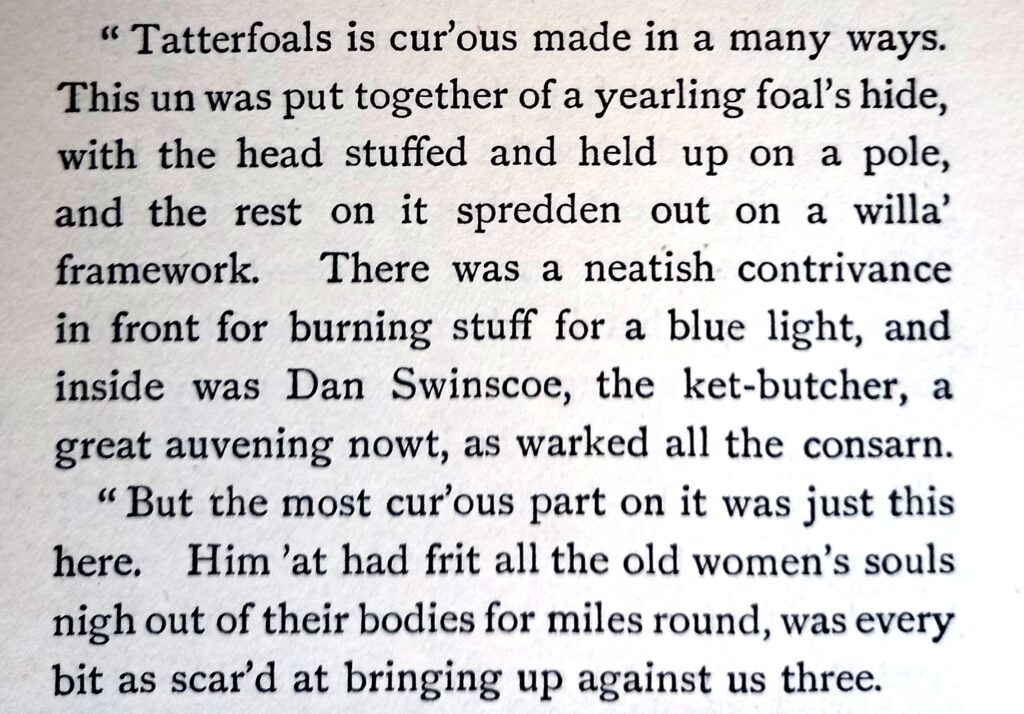

“Tatterfoal” references the Lincolnshire belief in a ghostly horse that waylays travellers on remote lanes. A youthful Eli Twigg and his mates decide that “this here wants looking into”, and lay a trap for the thing, which turns out to be a local ne’er-do-well dressed up like the hobby horse from a plough jag. Amateurishly disguised as ghosts themselves, the boys drag the “great auvening nowt” to a remote (supposedly haunted) spot and teach him a lesson.

Otchins

A ‘prickly-otchin’ is a dialect hedgehog, and in “Th’ Otchin ’At Wasn’t Nivver Suited Wi’ Nowt” (Taales pp.58-64) Mabel gives us the fable of an especially grumpy example who has an obliging fairy turn his spines into a lovely lamb’s fleece. Inevitably, it doesn’t turn out for the best: the moral is clearly, “don’t discard the blessings you already have”.

The fable, a hyper-short story with an obvious moral, usually featuring anthropomorphised animals, obviously appealed to Mabel. Aside from writing two of her own, she reworks eight of Aesop’s most famous. For example, in “Th’ Fox An’ Th’ Hoose-Dog” (Taales, pp.138-140) she recasts the dialogue between a wild ass and a tame horse learning that the grass is always greener to make her two protagonists sound more like poacher and gamekeeper. Not content with putting Aesop into dialect and giving him a local flavour, she usually changes or strengthens the moral to criticise selfishness, pride or overweening ambition. Her letters reveal that Mabel regretted the disruption to traditional social networks brought about by modern life, and the passing of a self-reliant connection to the land among all levels of society. Her fables are arguably where she critiques this most sharply.

In similar vein, her handful of traditional folktale retellings familiarise the fantastic and situate themselves in a realistic local milieu. Her home-grown protagonists face their adventures with native cunning. Thus, we have the farmer’s daughter (rather than the original princess) who outwits a violent suitor in “Th’ Lass At’ Seed Her Awn Graave Dug” (Tales & Rhymes, pp.72-75) which is based loosely on “Mr Fox”, a version of the Bluebeard legend.

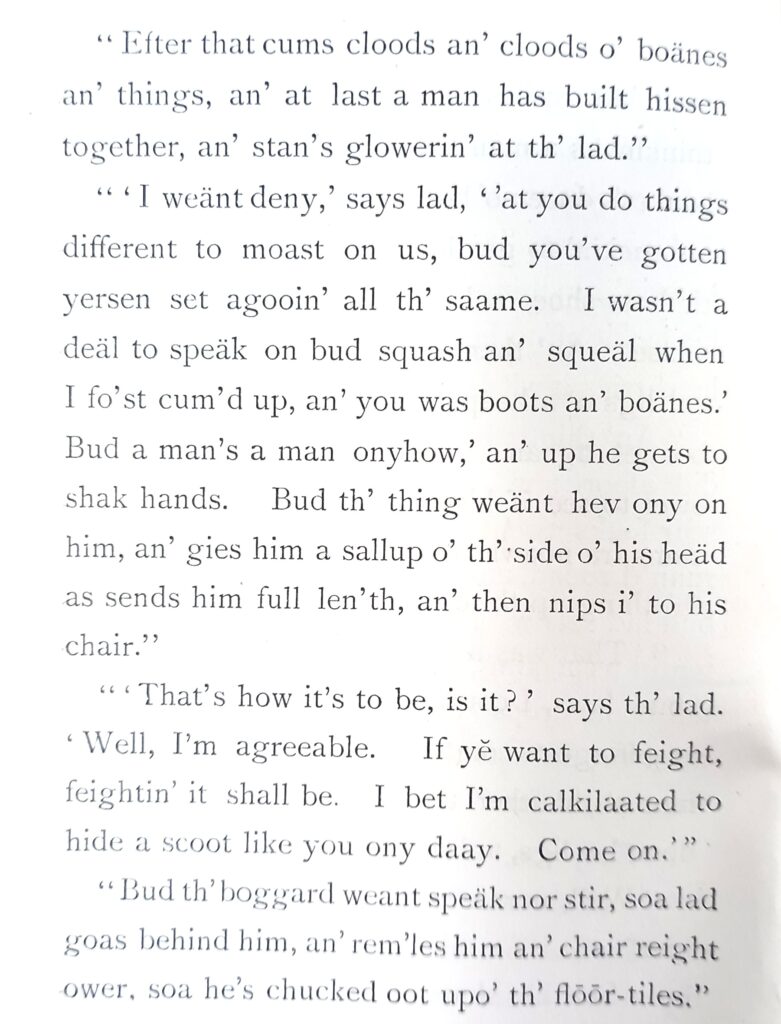

A laugh-out-loud account of Lincolnshire wit defeating recognisably Lincolnshire ghouls is in “The Lad ’At Wantid To Laarn To Shuther An’ Shak”, where the fearless hero exorcises a haunted windmill rather than a fairytale castle, including by tipping a giant skeletal boggard out of his chair; he marries the miller’s daughter instead of a king’s. (Taales, pp.119-133; based on the Grimm brothers’ “The Boy Who Went Forth to Learn Fear”).

A Pragmatic Manifesto?

Mabel may have had a social or intellectual agenda of sorts in her writing, or may have sought mainly to entertain. Either way, we should note that most of her stories are original, and it is unusual to find a Victorian woman writing original material entirely (or even substantially) in dialect. She wears her extensive folklore learning lightly, and where specific references are made they often add background colour or a subtle reflection on the main action. What’s notable in her fake-ghost stories are the rational, human explanations for superstitious terrors; even her versions of old folktales have their feet planted firmly on the ground. Evidently, ghosts and talking otchins are more believable if they sound local.

If we conclude Mabel had a message, it was one of rationalism, social cohesion and simple personal contentment – but it is, significantly, a lesson taught lightly, with great creativity and humour.

Focus On

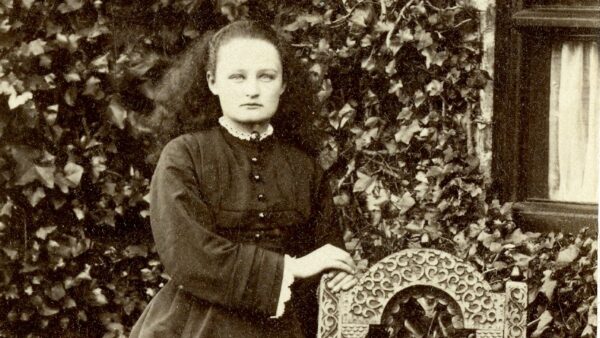

A Book-larnt Linkisheere Lass

Guest contributor Tim Davies attempts a character sketch of Mabel Peacock.

Read the story

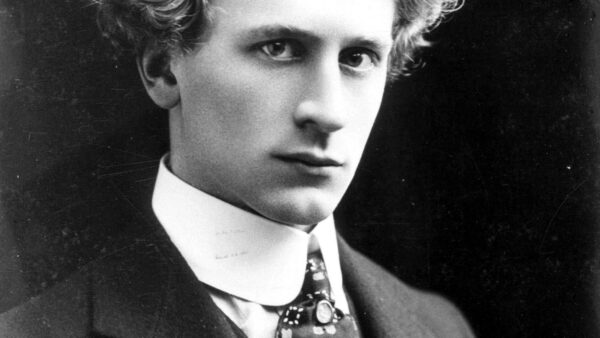

The Peacock Family

Discover the Peacocks. A family of distinguished scholars from Bottesford Manor.

Read the story

Curators Choice – Mabel Peacock’s Playscripts

A closer look at the six playscripts written by local folklorist Mabel Peacock of Bottesford Manor.

Watch the film

Folk Fishing in North Lincolnshire 1905 – 1908: Who Were the Folk that were Fished?

Guest author Helen Earl looks at the motives behind Edwardian folk song collecting in North Lincolnshire.

Read the story