Stories from the Stores

Jenny Kirton, Project Officer and the Dynamic Collections Project Volunteer Team

Introduction

Documenting Northern Lincolnshire’s History is a partnership project with North East Lincolnshire Museums running from December 2023 to November 2025. The project was made possible by National Lottery Heritage Fund, as part of their Dynamic Collections campaign. The Dynamic Collections volunteer team at North Lincolnshire Museum have been documenting and digitising objects from the Museum’s local history collections.

This co-produced exhibition spotlights stories from the Museum’s stores, chosen by the Documenting Northern Lincolnshire’s History project team. The exhibition was on show at North Lincolnshire Museum from May to November 2025. This article is an on-line version of that exhibition.

On 27 February 2024, a newly formed group of volunteers gathered at North Lincolnshire Museum, eager to begin an exciting project. The Documenting Northern Lincolnshire’s History project connects community members to their local history through objects in the collections. The team documents and digitises objects, uncovering stories along the way.

The stories in this exhibition centre around three key themes: community spirit, creative storytellers and community voices.

Why these themes?

- During our work, we discovered a strong sense of community spirit, from farming teams and fundraising carnivals to a grand-scale community opera.

- We identified fellow storytellers throughout the collections, each capturing parts of the past in creative and imaginative ways.

- We wanted to represent a variety of community groups and voices, as we recognised that certain stories were missing or underrepresented.

For us, as storytellers, the work has highlighted the importance of documenting all our voices and stories. We hope it encourages you to share yours with us too.

All Our Stories Matter

Six months into the project, our team had already worked with hundreds of objects from the Museum’s local history collections. We came together to talk about our experiences.

“I loved going through the ephemera boxes and discovering items that brought back memories from my past, like those of Scunthorpe High Street, the market, bus station, and other familiar places.”

Maxine Wilson, Dynamic Collections Project Volunteer

We spoke about why it is important to record our stories, how they connect people to places, and how many stories are still untold.

We are thrilled to share our fascinating discoveries with the wider community.

In this exhibition, we spotlight some of the stories that have inspired us whilst journeying back and forth through two hundred years of North Lincolnshire’s history. Alongside these stories, we offer a glimpse behind-the-scenes of our project.

Objects in the collections have mapped out routes into North Lincolnshire’s past, from marshlands, to farmlands and traces of ancient Roman settlements. We have investigated the area’s folklore and its many traditions, inspired by community spirit. We have been struck by its creative storytellers, and their legacies in music, literature and art. We have encountered its rich variety of voices, communities and cultures.

All of these factors have helped shape the North Lincolnshire we know today. And they remind us of our takeaway from the project: all our stories matter.

Mabel Peacock’s Playscripts

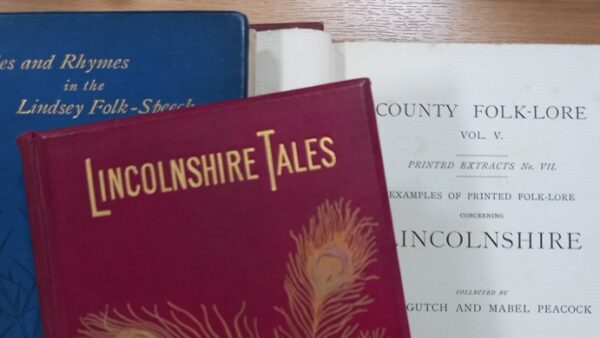

The local history collection contains the Peacock family archive. Some team members explored this archive and were especially interested by one family member, named Mabel Geraldine Woodruffe Peacock. Mabel recorded parts of North Lincolnshire’s local folk culture that could have otherwise been lost.

Mabel was born in 1856 and died in 1920. She was one of seven children born to Edward and Lucy Peacock of Bottesford Manor. She published research on local folk customs and Lincolnshire dialect. She was also a storyteller, known for her short stories and poems.

“Working with local studies librarian Tim Davies to learn more about our Lady Folk queen, Mabel Peacock, has opened my eyes to the breadth of her work and character. The phrase ‘lady folk’ can often be heard in conversations amongst our team. Local folklorists Mabel Peacock and Ethel Rudkin are the lady folk that inspired the phrase. For us, the phrase has come to mean the women that help define the folk culture of the local community.”

Holly Haines, Dynamic Collections Project Volunteer

During our research, we came across something unexpected. We discovered that Mabel also attempted to bring her storytelling to the realm of theatre.

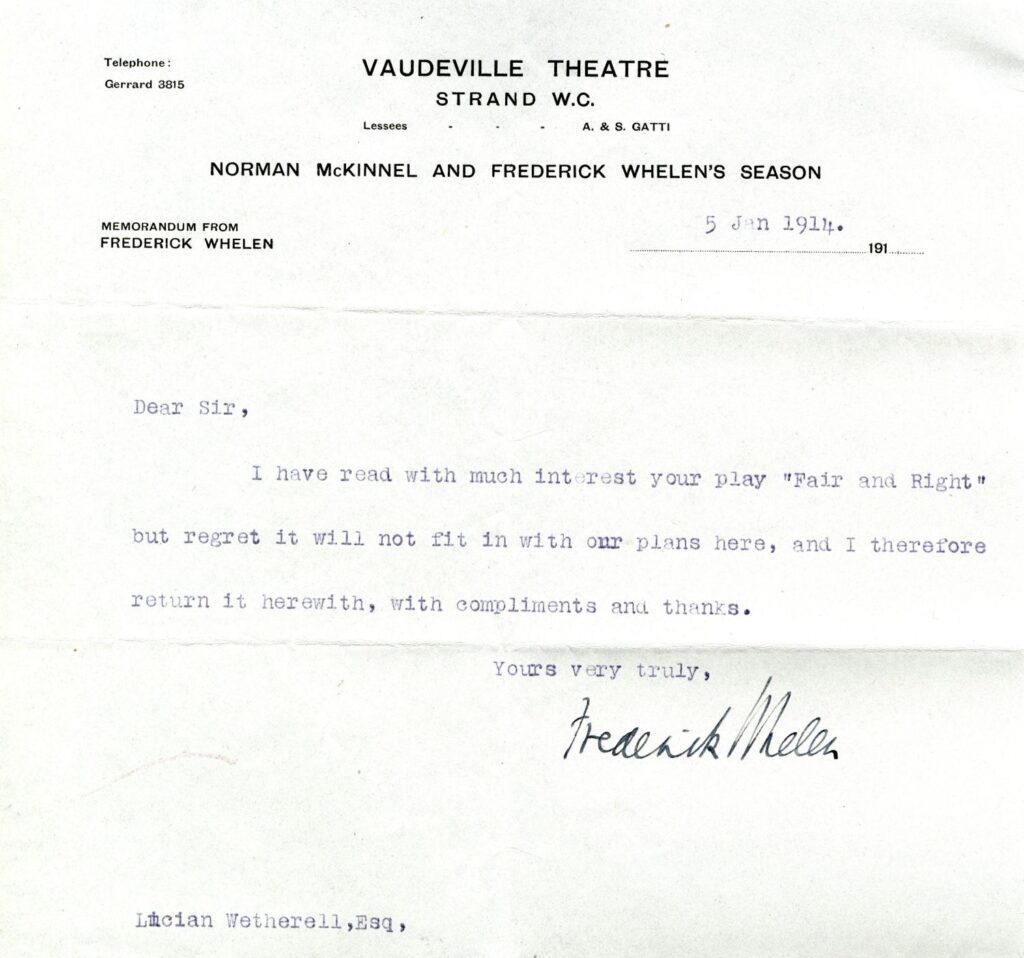

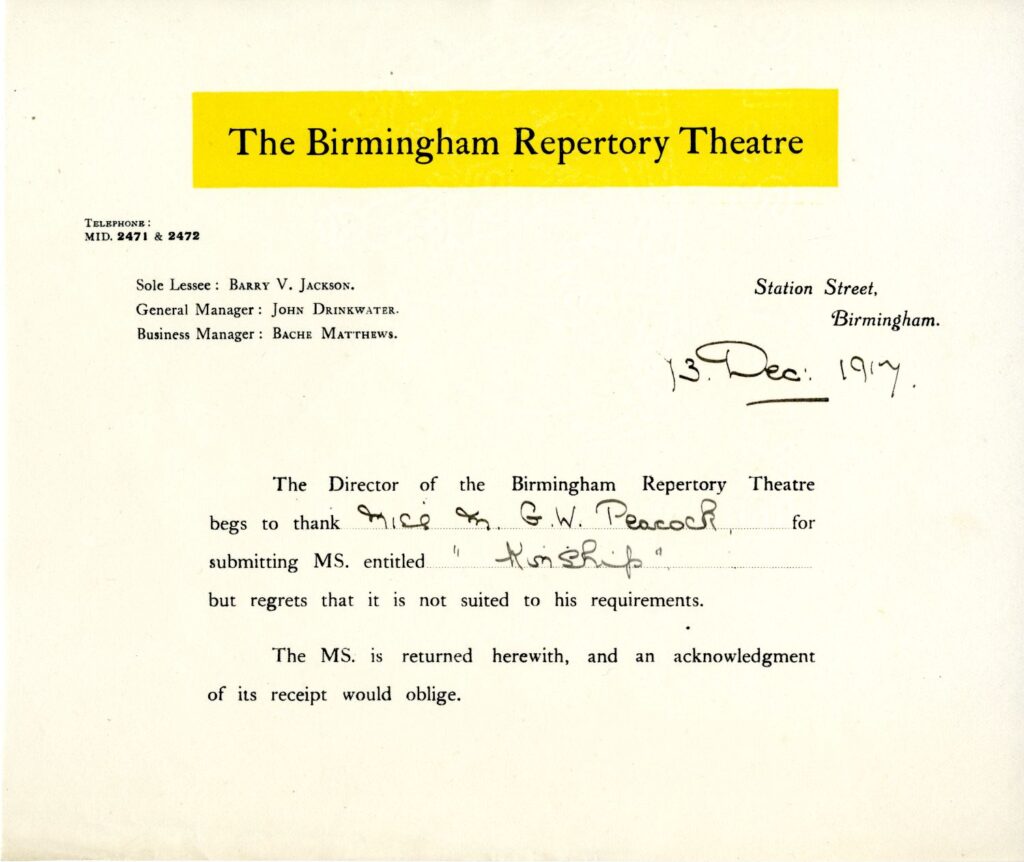

Mabel wrote six playscripts that feature local dialect. We cannot find evidence of the playscripts having been published or performed. However, the materials do indicate her desire to have them staged.

In another unexpected turn of events, we found a seventh playscript amongst the materials that created further questions. A playscript titled Fair and Right is credited to a “Lucian Wetherell”. But try as we might, we cannot find Lucian Wetherell. We searched the Peacock family tree, census records, and the Peacock archive.

Was Mabel writing under a different pen name? Or is Lucian someone else?

“Searching for evidence to uncover the identity of Lucian Wetherell has been both fascinating and challenging. While we still don’t know Lucian’s identity for certain, playing detective has been one of my favourite parts of volunteering!”

Holly Haines, Dynamic Collections Project Volunteer

Farming Folk: the Museum Makers Explore North Lincolnshire Farming Stories

North Lincolnshire is a largely rural area, and farming has played a very important role in its development. We even have a few farming folks amongst our Museum Makers team.

“In my 20s I worked at a pig farm. My job was feeding and mucking out the pigs.”

Sam, Museum Maker Volunteer

“My aunt and uncle had a farm, with pigs and potatoes. The geese chased me, and I was frightened.”

Darren, Museum Maker Volunteer

“Next door to my aunt and uncle’s farm was a pig farm. Me and my sister would jump a ditch to see the piglets.”

Sharon, Museum Maker Volunteer

We explored farming-related objects and photographs in the local history collections. This led to lots of conversations around our own connections to farming. We identified themes of family, community and the circle of life.

“My grandad worked in farming. He told me all his farming stories. I helped feed baby lambs on a working farm.”

Michael, Museum Maker Volunteer

From workers farming the land to markets and agricultural shows, our region’s farming history is deeply rooted in community spirit – alongside cereals, potatoes, sugar beet and livestock!

We have enjoyed learning about changes in farming techniques and the use of machinery. We have linked with a local farmer, who shared his experiences of farming and encouraged us to share our own farming tales.

“I attended Bishop Burton Agricultural College. I worked with horses, ducks and chickens. Then I took up Horticulture.”

Adam, Museum Maker Volunteer

“My cousin and uncle own a farm. I sometimes help them in the hay season. I saw the Christmas Tractor Run this year and I really enjoyed it.”

Peter, Museum Maker Volunteer

“Our neighbours had a dairy herd. After milking, the churns were placed by the road for collection. I gathered eggs. These were stored on the cold larder shelf.”

Ruth, Museum Maker Volunteer

Based on our collections research and the museum displays, we created a gallery trail. For the trail, we imagined ourselves as farming characters and planned our own farm.

Carnival Time: Give Well to Get Well

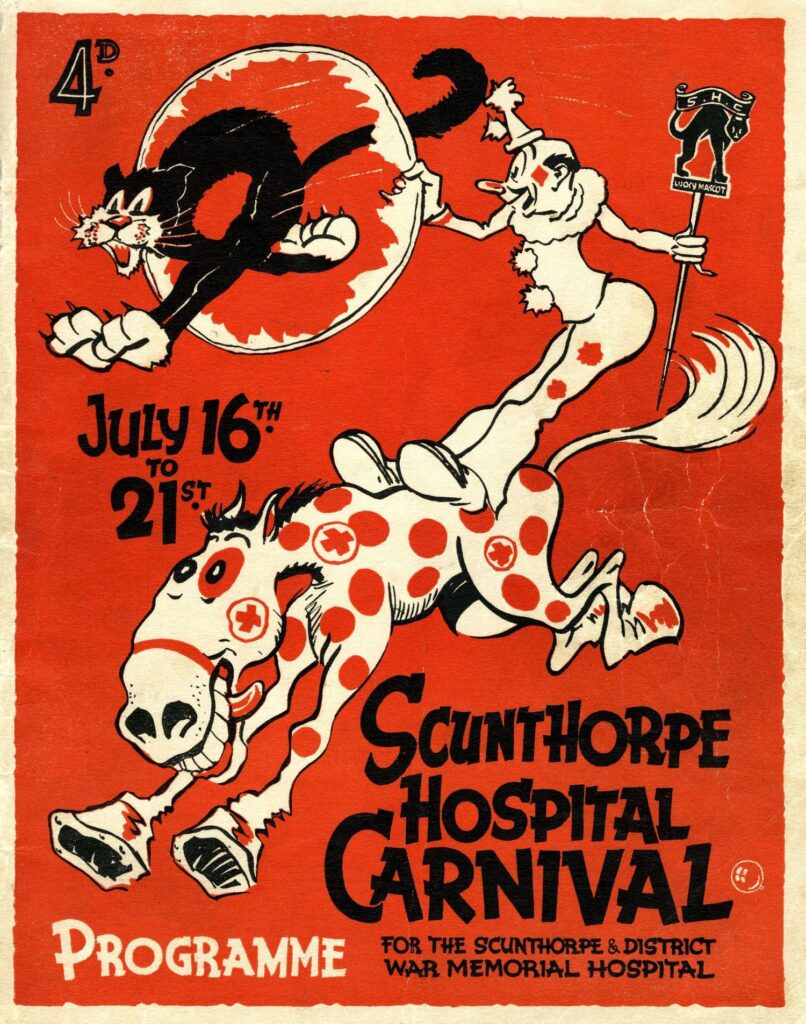

We came across a curious programme for the Scunthorpe Hospital carnival of 1932 in the collections. The programme left an impression on us. The cover was bright and playfully illustrated with circus characters. Marvellous celebratory plans were promised in its pages.

What stories might we find about Scunthorpe Hospital carnival week and how did the carnival begin?

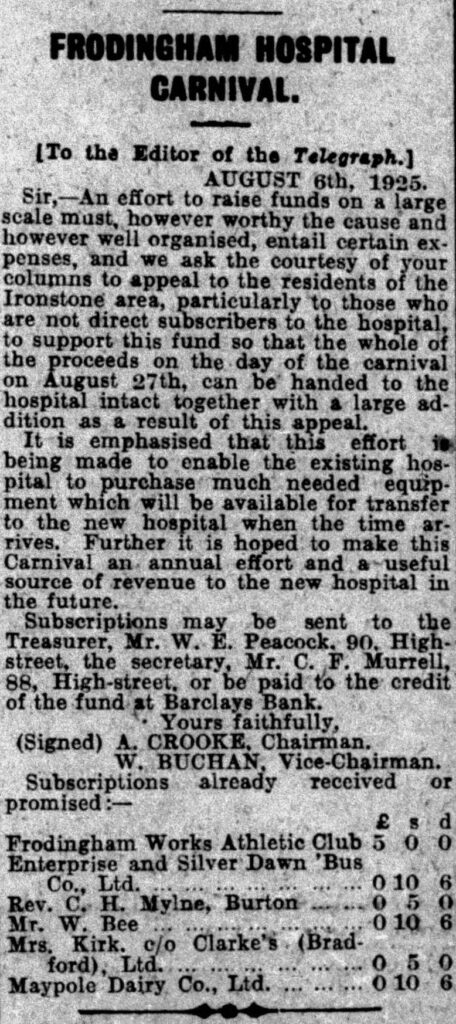

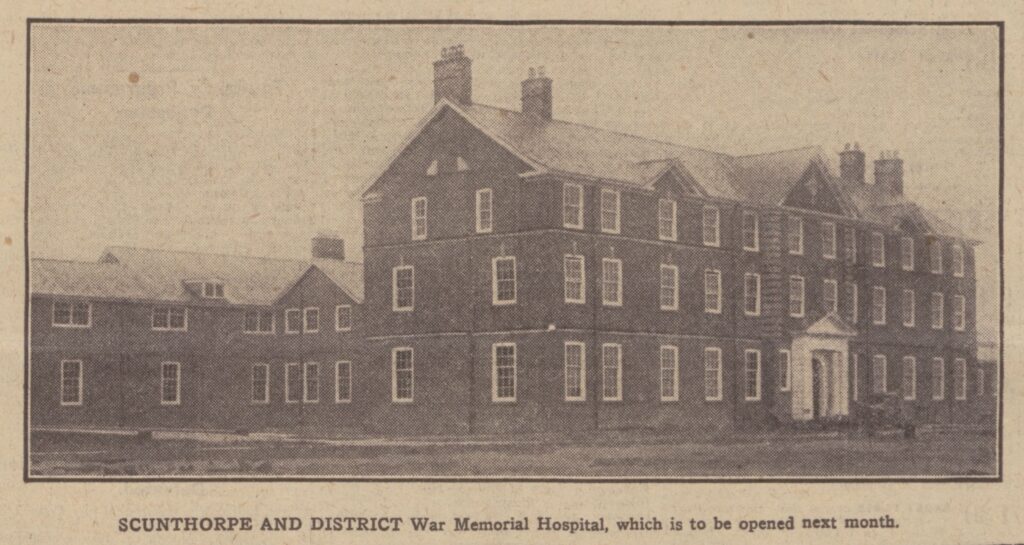

After the First World War, the formation of the Appleby-Frodingham Steel Company led to the growth of Scunthorpe. As the need for medical care increased, Frodingham Hospital became unable to meet the growing demands. The National Health Service (NHS) did not yet exist, so the responsibility for funding a new local hospital fell solely on the local people.

One of the main fundraisers was the annual hospital carnival, first held in 1925. Throughout the week there were numerous events, including the Crowning of the Carnival Queen, appearances by famous guests, a parade of floats, concerts, dancing, boxing tournaments, side shows and ox-roasts. It was a wonderful display of community spirit.

The War Memorial Hospital was finally opened in December 1929 and had 72 beds. The fundraising Carnival continued to raise money to support the running and development of the hospital for the next two decades.

From Coronets to Caring: Normanby Hall and Brocklesby Hall During the First World War

Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) hospitals provided care for injured soldiers during the First World War. By the end of the war, over 3000 stately homes and country houses and 90,000 volunteers had played their part.

During this period, two members of Northern Lincolnshire’s aristocracy swapped their coronets for nurse’s uniforms. They were Lady Julia Sheffield at Normanby Hall and Marcia, Countess of Yarborough at Brocklesby Hall.

Lady Julia Sheffield earned three service bars in total and was mentioned in despatches on two occasions: 14 August 1917 and the 29 January 1918. She was also awarded the badge of the Lady of Grace in 1918 for her voluntary work in the auxiliary hospital. On the 1 January 1920 she was awarded the O.B.E. She died 14 July 1952.

Lady Yarborough was mourning the death of her eldest son, Lord Worsley, when she set to work. Lord Worsley had only served for 24 days when he was killed at Zandvoorde, in Belgium, on 30 October 1914. Lady Yarborough’s courage and enthusiasm nonetheless helped other soldiers remain strong. In 1920, Marcia Amelia Mary Pelham, Countess of Yarborough was awarded an O.B.E. This was in recognition of her role as Commandant of Brocklesby Hall during the First World War. She died 17 November 1926.

Many of the patients were only in Brocklesby hospital for a few weeks. However, Private Scott, a soldier suffering from a gunshot wound to his right arm, was transferred to Northern General Hospital Lincoln after a stay of 236 days. The total number of soldiers convalescing at Brocklesby between 1914 and 1919 was 570.

At Normanby Hall, 1,248 soldiers were treated between 19 November 1914 and 10 January 1919. The number of hospital beds increased from an initial 25 to 75 by the end of the war. Patients came to Normanby Hall to recover from injuries that would require basic treatments, such as dressings for gunshot and shrapnel wounds. The soldiers’ stays could last anywhere between a few days and a few months.

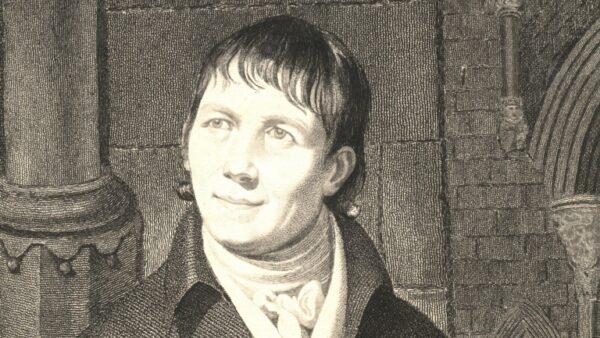

William Fowler’s Excavated Stories

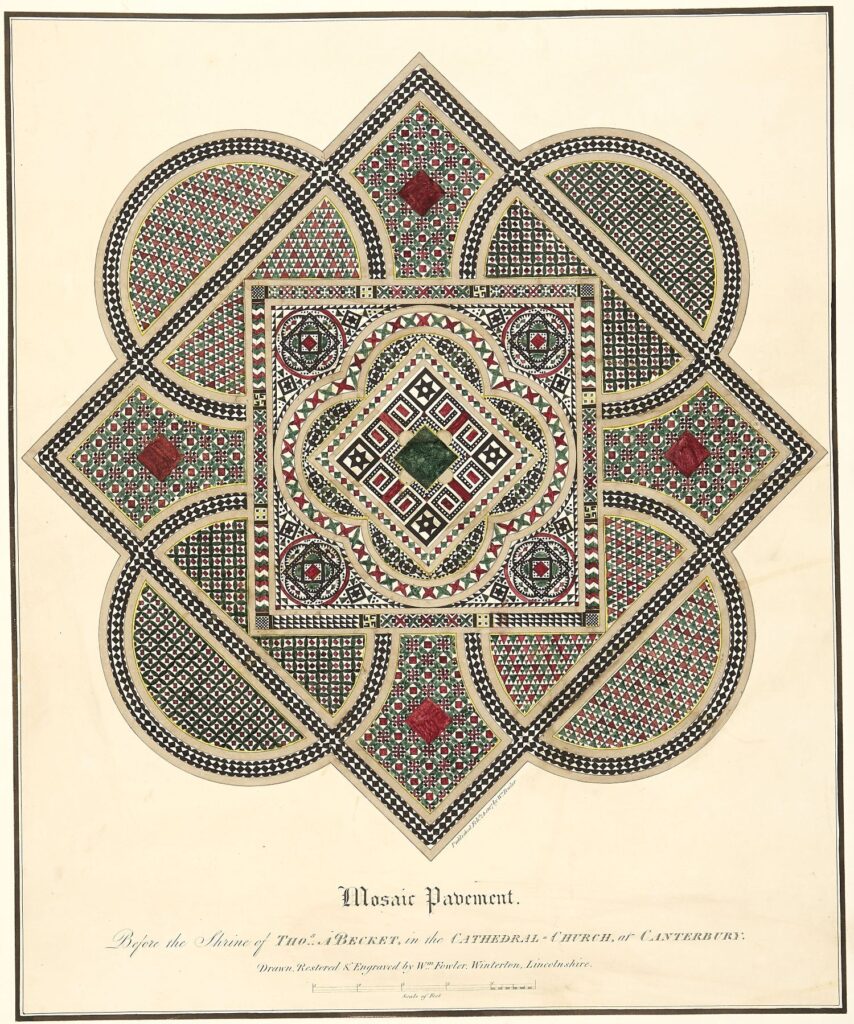

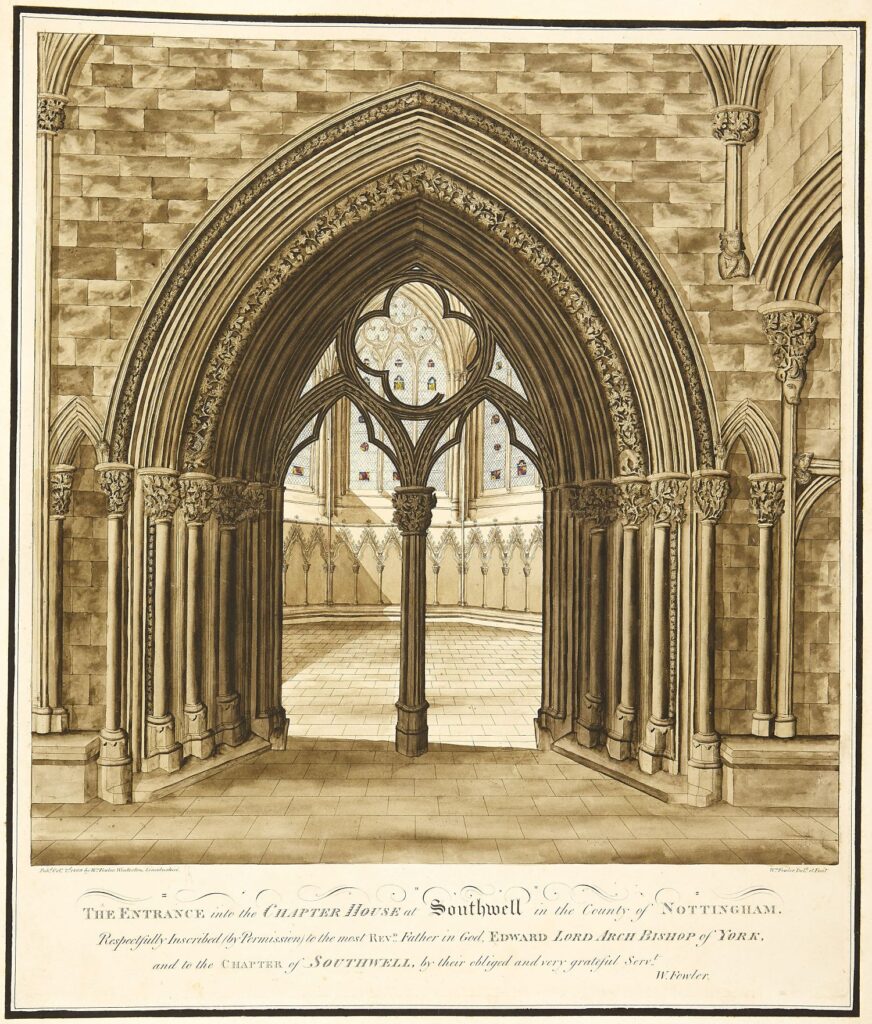

William Fowler was born in Winterton in 1761. He was a talented artist, known for his engravings of Roman mosaics and stained-glass windows. He was also a creative storyteller. He left a record of the past through his artworks and his letters.

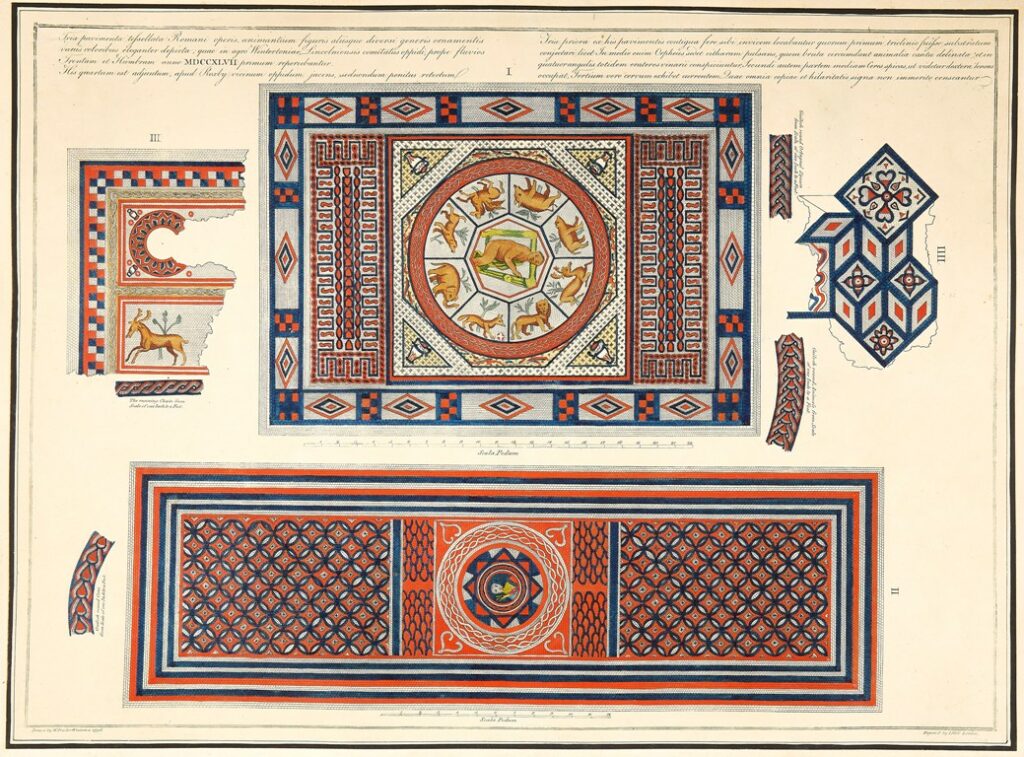

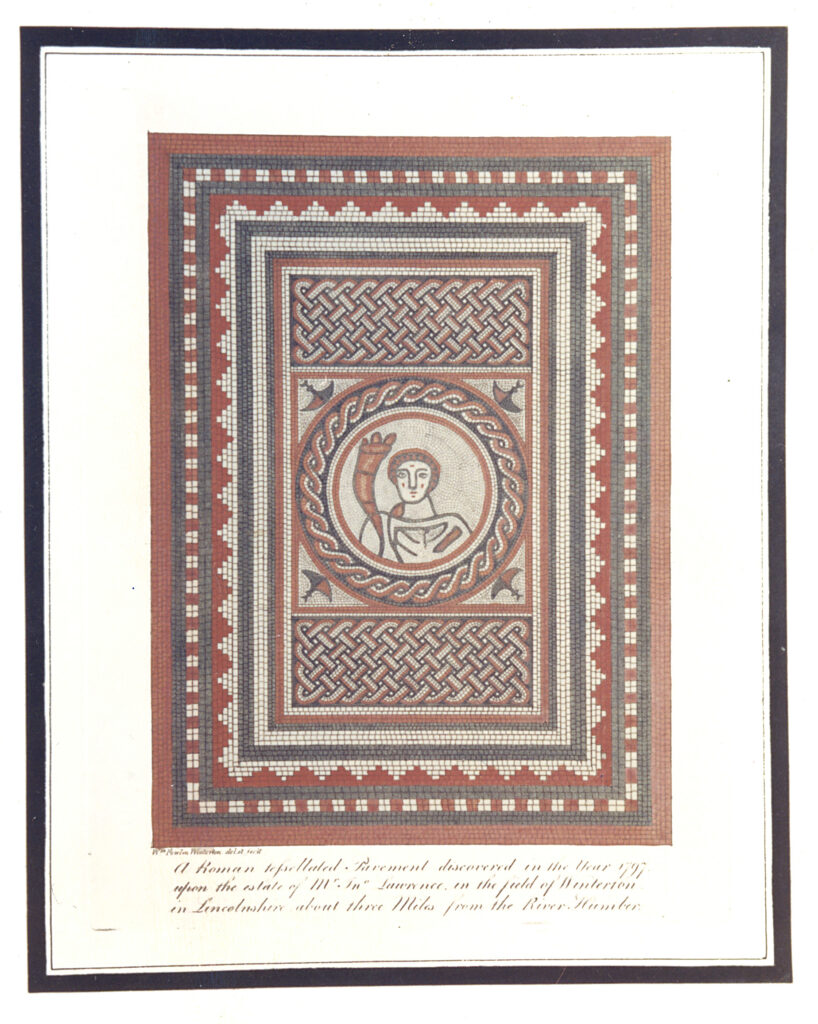

In 1747 two Roman pavements, known as the Ceres Mosaic and Orpheus Mosaic, were discovered in Winterton. The discovery of the Ceres Mosaic was reported to George Stovin, the Crowle antiquary, who visited and uncovered the remainder of the mosaic. He went on to locate and uncover the Orpheus Mosaic and commissioned an engraving from Charles Mitley and George Vertue. Though the mosaics were eventually reburied, whilst exposed both sustained damage from the weather and people removing tesserae as mementos. Indeed, George Stovin wrote to fellow antiquarian William Stukely about the Orpheus Mosaic and how he was “afraid the country people will deface it.”

Around 50 years later, Fowler became interested in the mosaics and made a copy of the Mitley and Vertue engraving. Wishing to check some details, he visited the site and re-exposed the mosaics. Fowler found that there were indeed errors in Mitley and Vertue’s engraving. He also seems to have found a badly damaged pavement – Stovin’s fears were well-founded.

When the Orpheus Mosaic was first uncovered, there was a central panel present showed Orpheus playing his lute. Mitley and Vertue’s engraving shows a vaguely man shaped creature. This panel appears to have been missing when Fowler viewed the pavement, as he did not make more accurate drawings.

Whilst visiting the site Fowler was forced to shelter in a ditch along with some passing boys during a rainstorm. The boys amused themselves poking mud with a stick and by happy chance discovered a third pavement, the Fortuna Mosaic, which is now on display in the Archaeology Gallery at the Museum.

When archaeologists returned to re-excavate Winterton Villa in the mid-20th century, they found a pit cut through the centre of the floor where the Orpheus panel should have been. A Victorian chamber pot had been left in its place. The chamber pot is on display in the Archaeology Gallery of the Museum.

Who had made the exchange? Does the missing panel still exist?

Fowler also left a record of his own life. His letters, published by his grandson, describe his Georgian-era jaunts.

Fowler went on numerous ‘sales trips’. Using introductions from various patrons, such as scientist Sir Joseph Banks, he took his portfolio of engravings. He encouraged his contacts to take out subscriptions for his engravings.

Fowler comes across as a very affectionate husband, father and brother in his letters. In one of our favourites, he describes his encounter with Queen Charlotte and the Princesses Elizabeth, Mary and Augusta at Frogmore House in detail. He wanted all his family to share in the experience.

Marjorie Duff’s Diaries

The local history collections contain 11 diaries written by Marjorie Duff, formerly Rust. Marjorie’s diaries are full of stories about life in North Lincolnshire, between the years 1926 and 1936.

Marjorie’s father was the vicar of Frodingham, Cyprian Thomas Rust. Her mother was Mary Rust, formerly Burton. Marjorie also had a sister and a brother, Cecily and John. The Rust family lived at Frodingham vicarage, which we now know as North Lincolnshire Museum.

The diaries show Marjorie’s life, from her teenage years through to marrying her sweetheart, Robert Duff, and starting her own family. Marjorie was born in 1908 and died in 1995. The earliest diary entry in the collection is dated Friday 1 January 1926. Marjorie goes to a ball in Lincoln and enjoys “a jolly good supper, including champagne.”

One of our favourite diary entries is from April 1934, Marjorie’s wedding day. We have a wedding photograph of Marjorie and her husband in the collections. In her diary, Marjorie writes that she walked down the garden and up the lane to the church, which was packed.

The diaries give a lot of information about Marjorie’s interests, hobbies, and general family life. She records everything from day trips to Christmas present lists. The diaries draw slowly to a close in April 1936, as Marjorie becomes busier as a parent to her baby son, Michael.

Historical Gaps and Stories Untold

The Museum’s collections include a variety of objects, holding countless stories. But what about the objects for which we know little or nothing of their stories?

Many of these unknown objects have global and colonial connections. Sometimes they represent a painful past. Sometimes they offer a final trace of stories that have gone unrecorded.

Our team is interested in whose stories are told and who gets to tell them. We recognise that these questions are connected to legacies of race and colonialism. We reflected on our responsibility as storytellers. We came up with questions to direct our storytelling:

- What can we do better to represent our local area?

- Whose voices are represented in our exhibitions?

- How do we address the gaps in the stories we share?

“I like that the museum’s local history collections call attention to the many cultures and customs that exist within our local communities.”

Archie Wood, Dynamic Collections Project Volunteer

Connecting and sharing objects with community members helps to reveal untold stories. Certain objects in the collections helped us to think about gaps in our recorded history. In some cases, we also explored stories connected to objects that are not in the Museum’s collections.

We came across the story of the schooner, Young Dick. The schooner’s story connects Burton-upon-Stather to a broader history of empire and colonialism. It was launched from Wray & Sons’ yard in Burton-upon-Stather on 28 June 1869. It sailed to Polynesia, as part of the South Sea labour trade, which involved the exploitation of Indigenous populations.

North Lincolnshire’s Polish Community

The historic movement of people to and from North Lincolnshire is an important part of our region’s story. During our research, we came across newspaper clippings documenting the important role played by the Polish Air Force locally during the Second World War.

Following the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, many Polish people were displaced from their homeland. These included prisoners, refugees or people serving in Poland’s armed forces. Many made North Lincolnshire their home.

“I had known that the local area was significant to the RAF, with various airfields and bases scattered throughout the nearby countryside. I realised that a topic many might not know about is the role European allied forces played in the air, with North Lincolnshire serving as their temporary home.”

Dan Zetterstrom, Dynamic Collections Project Officer

Lincolnshire was an important location for the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. It was often referred to as Bomber County. Airfields and bases brought together workers of various nationalities. The airfield at Blyton was first used by the Polish Air Forces for training in 1943. Polish bomber squadrons were also stationed at RAF Hemswell and nearby overflow airfield, RAF Ingham.

In 1947, the Polish Resettlement Act was put into place by the British government. This would assist Polish people in a variety of ways with citizenship, employment, health services and accommodation. Many were temporarily housed in resettlement camps in North Lincolnshire, like Elsham Wolds and Luddington.

The steelworks became an attractive option for those searching for work. There are many stories of success and hope. Individuals such as Michael Gorne and Napoleon Szenher, who opened S & G Stores, created thriving businesses. We are proud to celebrate North Lincolnshire’s Polish community, both past and present.

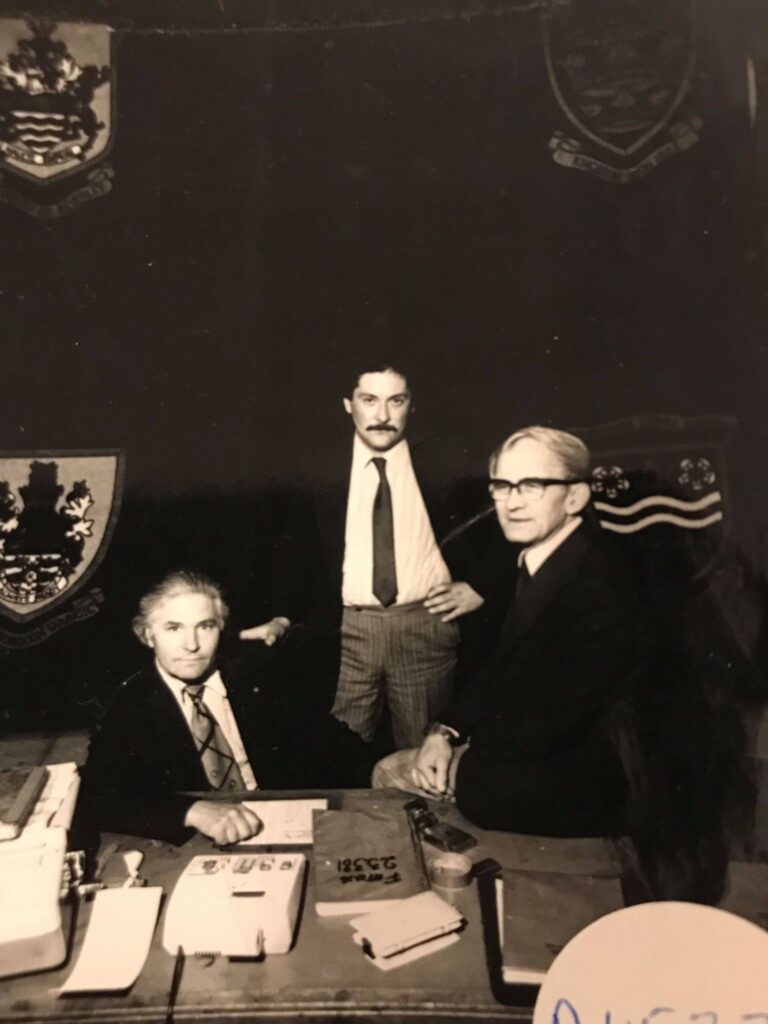

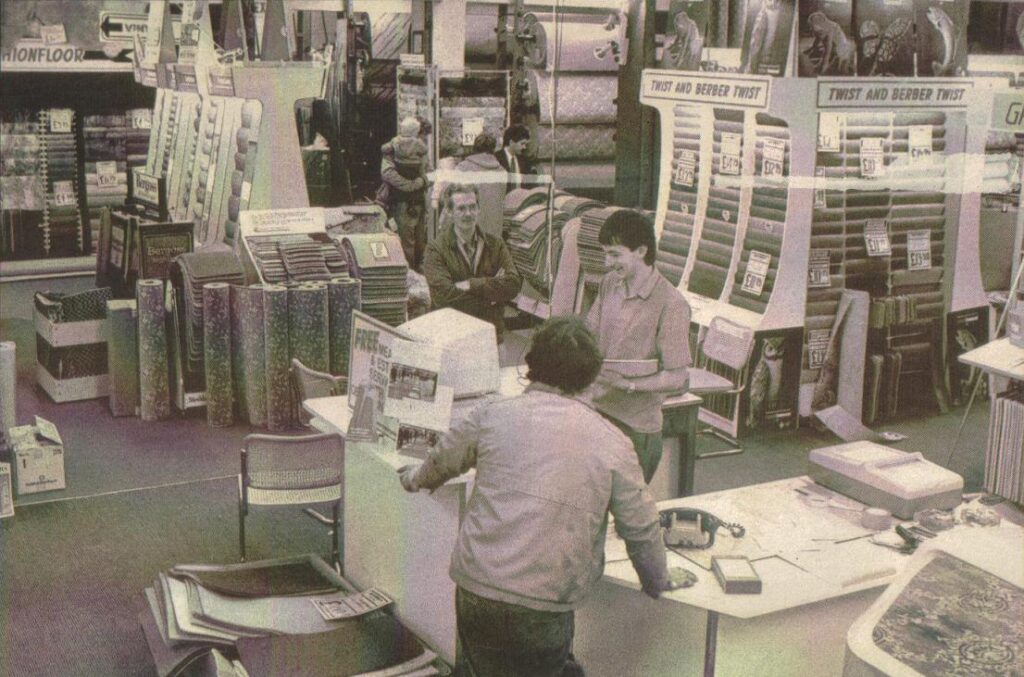

The Men Behind Scunthorpe’s S & G Stores

Many locals may remember S & G Stores, which traded in Scunthorpe between 1952 and 1993. We wish to shine a spotlight on Napoleon Szenher and Michael Gorne, who set up S & G Stores.

“Generations have furnished their homes with S & G Stores. We thought it was a very important part of the social history of the area, so needed to be included in the exhibition.”

Maxine Wilson, Dynamic Collections Project Volunteer

Szenher and Gorne were two remarkable Polish ex-servicemen who moved to Scunthorpe in the post-war period. Both men had spent time in prisoner of war camps during the Second World War. Gorne had been part of the Polish underground movement. He was captured and spent time in German and Austrian prisoner of war camps.

Szenher, after being released from a prisoner of war camp by the Allied forces in 1945, had initially joined the Polish Second Corps in Italy. He was transferred to the Polish Resettlement Corps and subsequently came to England in 1946.

The pair started S & G Stores with very little. They sold ex-army surplus, such as war grave wooden crosses and American steel helmets.

Together with other Polish men, Szenher and Gorne built their first S & G store on the corner of Scunthorpe High Street and Home Street in 1952. Over the next few decades, they developed an extremely successful business. More store openings followed in Scunthorpe, but also Leeds and Huddersfield.

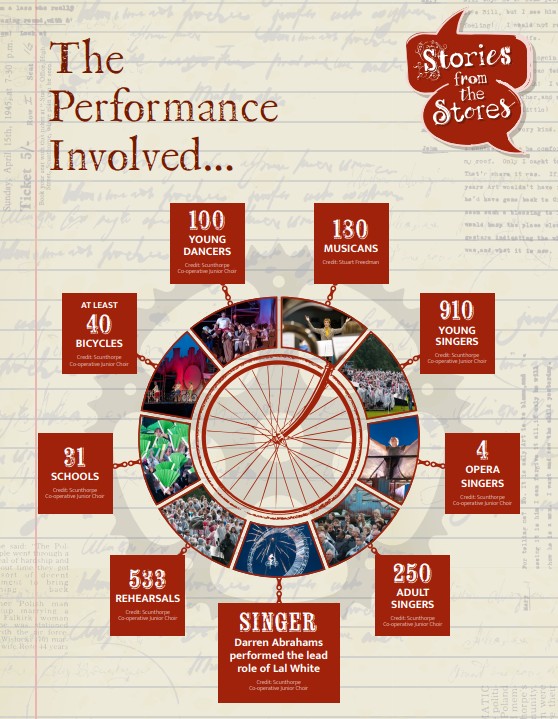

Spirit of Steel: Remembering Cycle Song

On a rainy weekend in July 2012, over 1,200 performers gathered at the Brumby Hall grounds in Scunthorpe. Here, they performed the story of a celebrated Scunthorpe cyclist, Lal White, to an audience of thousands.

Cycle Song was a community opera that brought together local choirs, schools, drama students, musicians and professional singers. The production was performed on 14 and 15 July 2012. It was a collaboration between Scunthorpe Co-operative Junior Choir and Proper Job Theatre to mark Lal White’s achievements.

“I was amazed and delighted how the musical community of North Lincolnshire stepped up and volunteered to take part in Cycle Song. They came in their hundreds.”

Susan Hollingsworth, Scunthorpe Co-operative Junior Choir

We were delighted when we came across the Cycle Song musical score in the Museum’s stores. We shared memories of the production between us and asked community members to share theirs.

“Our interest in Cycle Song began when one of us came across articles about Albert ‘Lal’ White and became intrigued by his achievements. Meanwhile, two other volunteers had just come across some programmes for Cycle Song. With these materials, our research journey began.”

Sally Baker, Dynamic Collections Project Officer

We discovered that the rainy weather during dress rehearsals created lots of challenges. Choreography had to be altered as performers could not cycle up slippery ramps. A crane, needed to lift scenery, could not access the grounds. Although the dress rehearsal was a wash out, it luckily didn’t rain for the performances.

“Cycle Song shone a spotlight on North Lincolnshire as somewhere where exciting, creative events can happen and leaves a lasting legacy in the local area and beyond.”

Scunthorpe Co-operative Junior Choir

The creators of Cycle Song set out to capture Scunthorpe’s spirit of steel. Now, over a decade later, we are proud to gather memories of a performance born through our area’s creativity and community spirit.

More to Explore

Documenting Northern Lincolnshire’s History Project

National Lottery Heritage Fund project Documenting Northern Lincolnshire’s History.

Read the story

Curators Choice – Mabel Peacock’s Playscripts

A closer look at the six playscripts written by local folklorist Mabel Peacock of Bottesford Manor.

Watch the film

Otchins, Ghosts, and a ‘tater For Rheumatism: Mabel Peacock’s Dialect Tales

Guest contributor Tim Davies with an introduction to some of the little-known dialect stories of Mabel Peacock, with a look at the use of folklore and tradition in her writing.

Read the story

William Fowler of Winterton

On-line exhibition charting the life and times of architect and antiquarian William Fowler of Winterton (1761 – 1832).

Read the story

Museum Makers Choice – Marjorie Duff

Join Museum Maker Sam for a closer look at the diaries of Marjorie Duff, who lived at Frodingham Vicarage.

Watch the film