William Fowler of Winterton

Rose Nicholson, Heritage Manager

The Fowlers of Winterton

William Fowler was born in Winterton on 12 March 1761. Although trained as a joiner, he became well known for his coloured engravings of Roman mosaics and stained-glass windows.

William Fowler of Winterton

His family had lived in Winterton since at least the seventeenth century. William Fowler himself was the eldest of twelve children born to Joseph and Mary, five of whom died as children. His father Joseph Fowler was the village carpenter. William Fowler attended the local school, where he was taught by Master Teanby.

On 23 May 1790 William Fowler married Rebecca Hill. They had five children, though three died of consumption. Only Joseph and Mary Ann were still alive when William died. Mary Ann died in 1858 at Ripon where her son William Fowler Stephenson kept a boarding school. Joseph died in Winterton on 2 April 1882, at the age of 91.

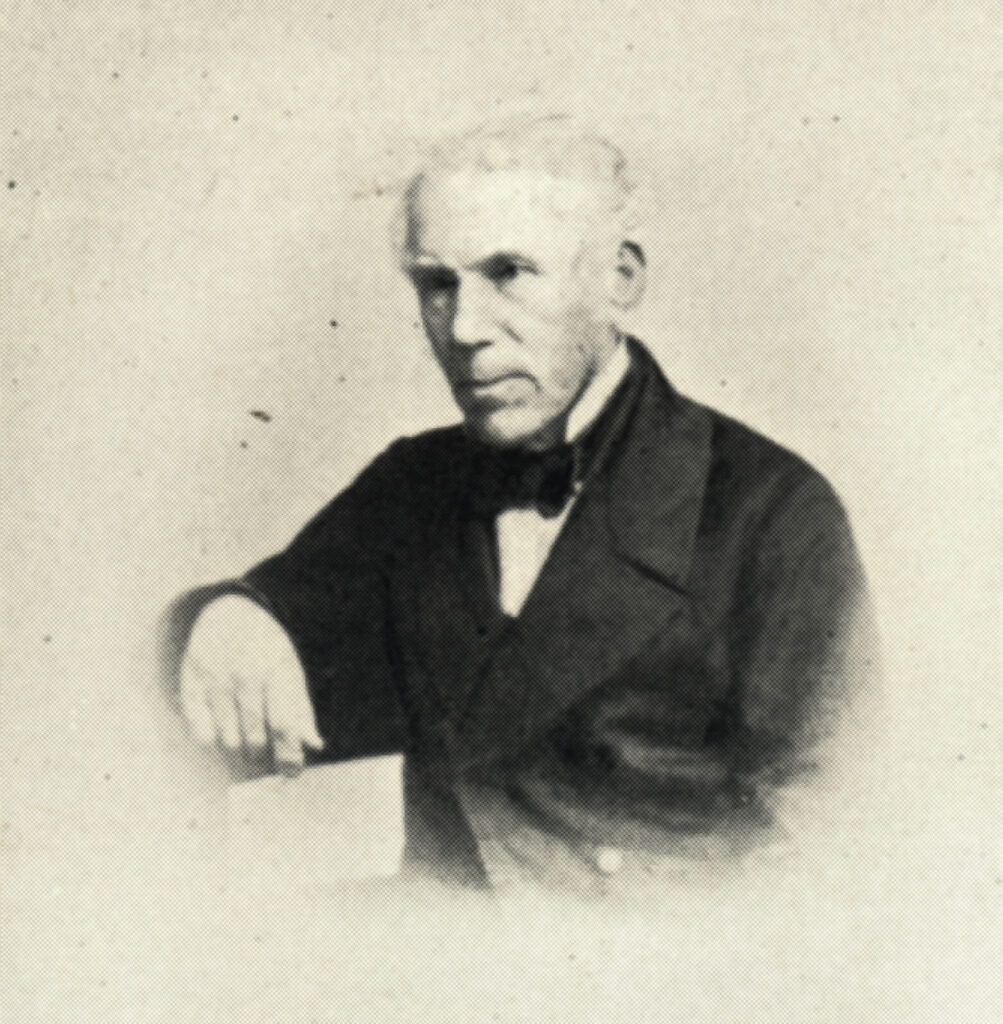

William’s letters were published by his grandson Canon Joseph Thomas Fowler, son of Joseph Fowler. These letters show him to have been kind, affectionate, generous, witty, and very devout.

William Fowler died on 22 September 1832. As he requested, he was buried under a cruciform slab marked only with his initials and the date of his death, near the south door of Winterton Church.

William Fowler and His Times

During William Fowler’s lifetime Britain had endured thirty years of war with France and the destabilising effects of the French Revolution. Many Britons sympathised with the Revolutionaries.

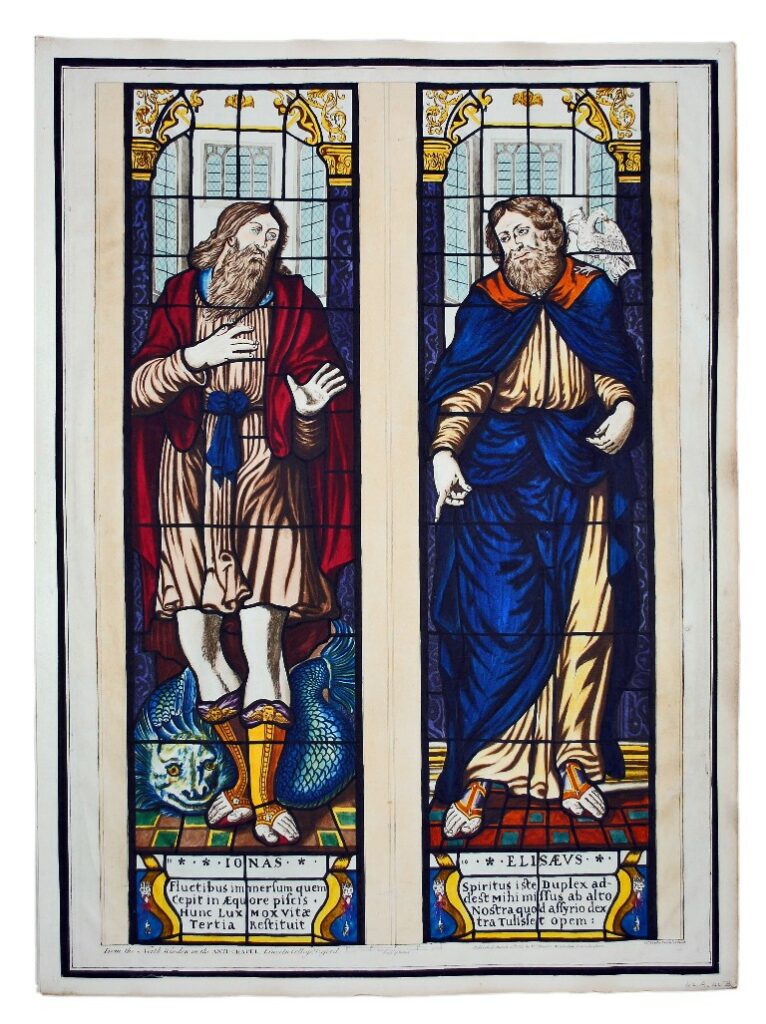

During the Revolution, French church buildings were stripped of their contents. The fittings such as stained glass and carvings were removed and sold. Many pieces of Medieval glass were brought to Britain and used to replace church glass destroyed by Cromwellian soldiers during the English Civil War of 1642–1651.

Despite social unrest and economic pressures at home caused by the War, Britain finally defeated the French in 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo and emerged as the nineteenth century world power. One of the side effects of years of constant war with France was a growing appreciation of home-grown antiquities. Because of wars in Europe, it became increasingly difficult for young English gentlemen to complete their education with a “Grand Tour” of the Italian States and Rome. Instead, they turned their attention to Romano-British remains, particularly the surviving mosaic floors of Roman villas.

They also began to look more closely at other ancient remains in Britain and Gothic architecture caught their imagination. At this time, it was believed that all Gothic building was Saxon or Norman in origin, and therefore much closer to the Romans in date.

The fascination with everything Gothic was to change the style of English architecture. After about three hundred years of building in a style inspired by Classical Rome, Englishmen began to try to build in a Gothic style. Gothic revival architecture included crenellations, towers, arched and leaded windows, and iron-studded doors. The first notable house in this style was Strawberry Hill, built in 1753 by Horace Walpole, fourth son of the Prime Minister.

Fowler and Methodism

The cultural and social changes which took place during the Georgian Period saw new ways of thinking develop which influenced religious attitudes. Though a member of the Church of England, William Fowler was a prominent figure among local Wesleyan Methodists.

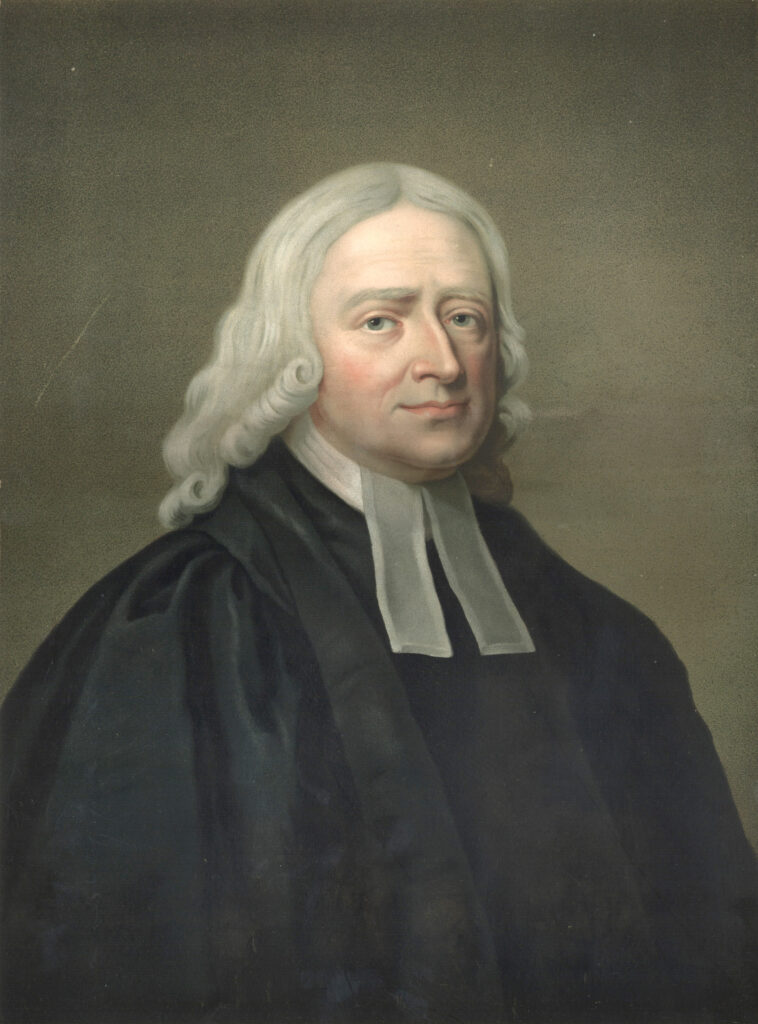

The Methodist movement was founded by Charles and John Wesley of Epworth. They preached a message of salvation for all who put their faith in Christ. Initially Methodism was a reform movement within the Anglican Church. Followers attended their parish church as well as local Methodist meetings. When John Wesley died, the final break with the Anglican Church followed.

As a young man, William’s father Joseph joined a group of Methodists who met at Katy Keyworth’s house. William Fowler took after his father, welcoming Methodist preachers into his home. His grandson recorded how “during the whole of his adult life he was a member of Mr Wesley’s Society and during a great part of it a class leader, but he remained faithful to the Church from first to last, never missing any service when at home”.

Methodists were taught to preach and encouraged to help others through charitable work. John Wesley told members to ‘Make all you can, save all you can, give all you can’. The ability to speak in public and to manage money were two skills William Fowler would have found useful when developing his business.

William Fowler and Georgian Society

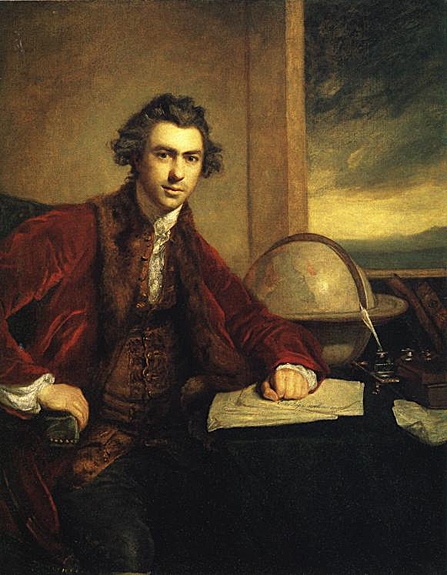

William Fowler began as a joiner in a Lincolnshire village but through his work he met many notable people. These included Sir Walter Scott “the Wizard of the North” and famous scientists like Sir Joseph Banks. His greatest moment was being presented to the Royal Family at Windsor Castle.

Fowler’s first patrons were Dorothy and Thomas Goulton of Walcot Hall. He first came to their attention when Thomas Goulton saw a piece of his wood carving in Reverend Gilby’s drawing room at Winterton. The Goultons helped Fowler with introductions to their society friends, gaining him access to both subjects and buyers for his engravings.

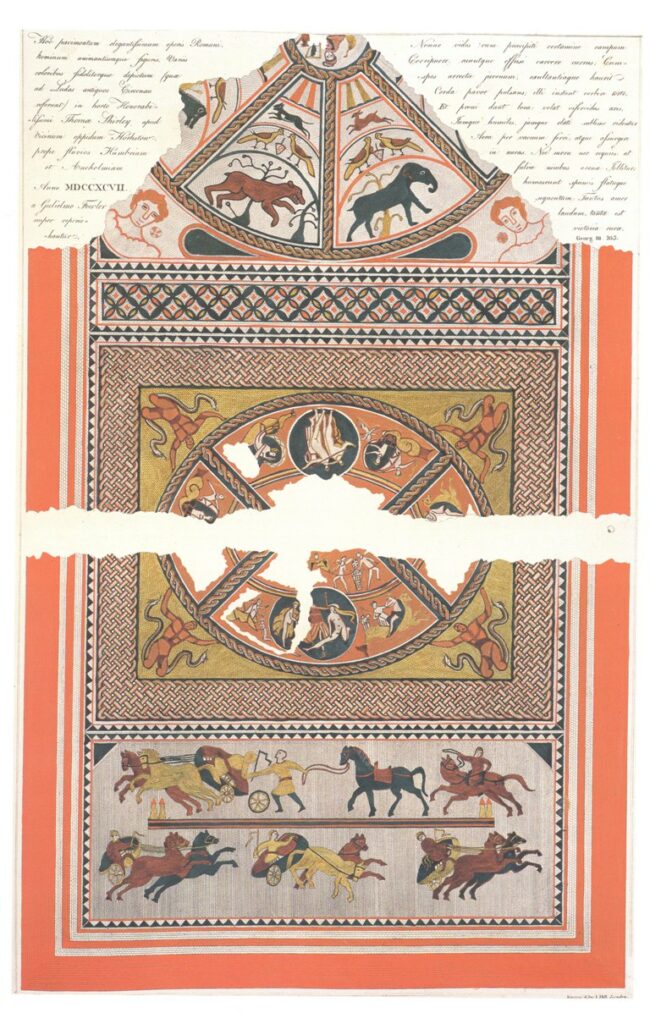

Sir Joseph Banks was another early friend and patron. Banks showed Fowler’s drawings and engravings to influential people including the Society of Antiquaries. In 1797, Fowler wrote to his wife from London of how he had shown Banks his Horkstow Mosaic drawing. Banks declared it to be “the finest drawing and the handsomest pavement he has ever seen”.

The Goultons knew the Royal Family through Dorothy’s father Leonard Smelt, tutor to the Prince Regent. These connections enabled Dorothy to arrange an introduction for William Fowler to Queen Charlotte and Princesses Elizabeth, Mary and Augusta at Windsor Castle. On one visit William Fowler displayed his engravings to the ladies and presented copies of his drawings. Queen Charlotte’s page took him to look at Frogmore, and he sent home a detailed account of his visit.

Whilst William Fowler was with the Royal family, the Queen sent for Francis Willis, physician to King George III. As Willis was a Lincolnshire gentleman, Queen Charlotte thought it would be pleasing to both gentlemen to have an interview.

William Fowler first met the author and poet Sir Walter Scott in Edinburgh. He also went to Abbotsford and met Sir Walter and his dogs in the grounds. Whilst they looked at his engravings, William Fowler noted that Sir Walter was more interested in the painted glass and other medieval subjects than the mosaic pavements.

William Fowler, Builder and Architect

William Fowler earned his living was as a builder and architect. From an early age he showed great skill at carving and using a lathe. His father Joseph was the village carpenter. After leaving school William was apprenticed to the family firm.

The business was run from a large workshop attached to the house. It was said that, “He was never defeated in accomplishing any work brought to him, and would surmount any difficulties, sometimes in a very original manner”. By the end of his career he employed a large staff of journeymen and apprentices which included his three sons. The apprentices lived with him and his family at 53 West Street.

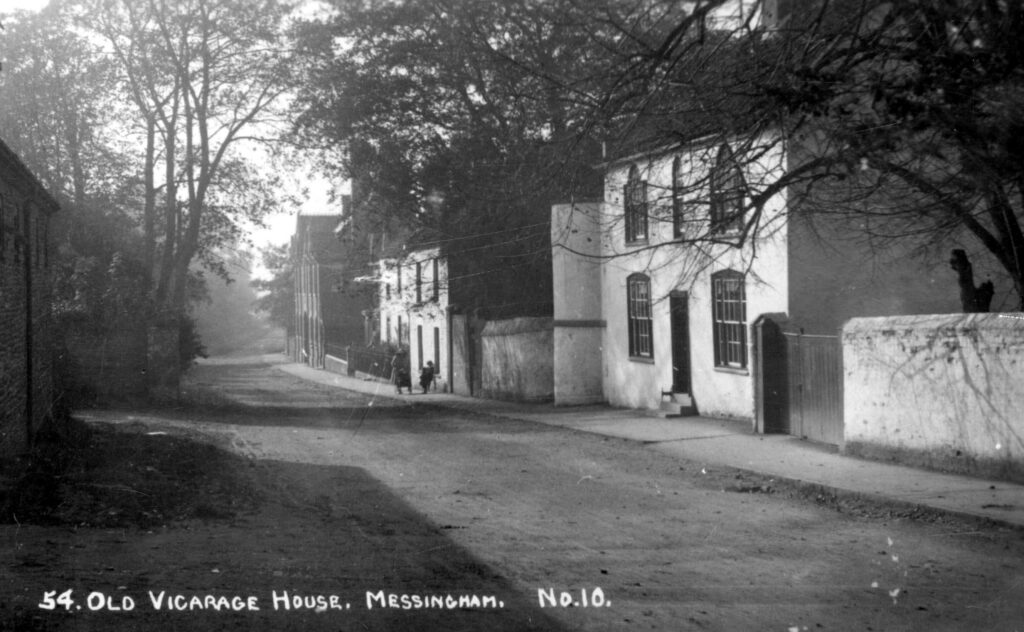

Fowler sometimes worked as a clerk of works. His architectural work seems to have taken off after he published his first engravings in 1796, possibly because of the contacts he made. The term “architect” was more fluid than it is today. It included experienced builders like Fowler who worked from local tradition and pattern books. His architectural work ranged from church restorations and alterations, to farmhouses, vicarages and schools. The majority of this work was in Lincolnshire, and mainly in the north of the County.

William Fowler’s Engravings

As a young man William Fowler developed antiquarian interests encouraged by George Stovin, a local antiquary. By the end of his life he had produced at least 116 engravings of subjects including Roman mosaics, stained glass and church architecture.

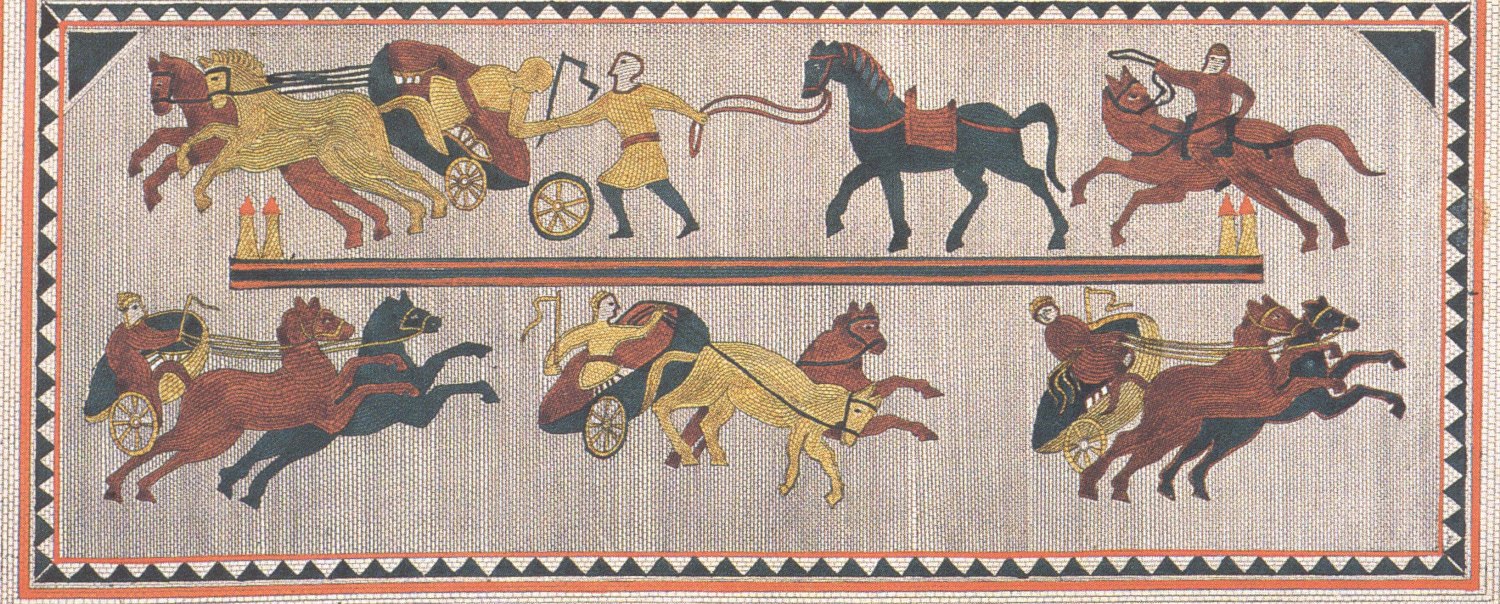

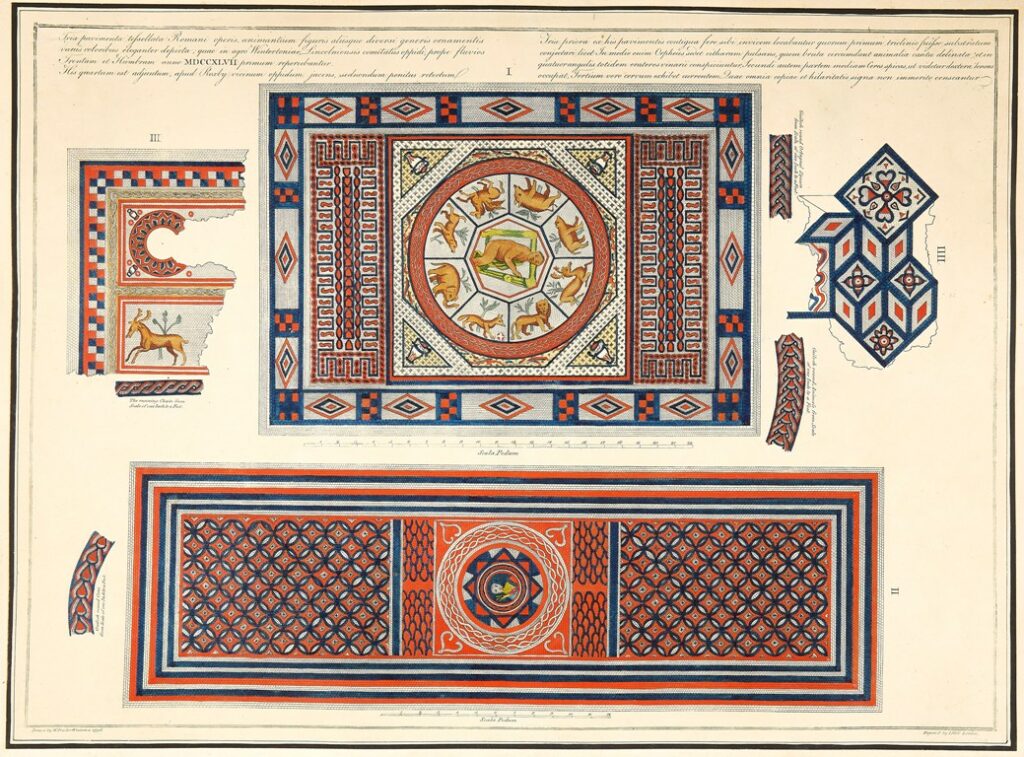

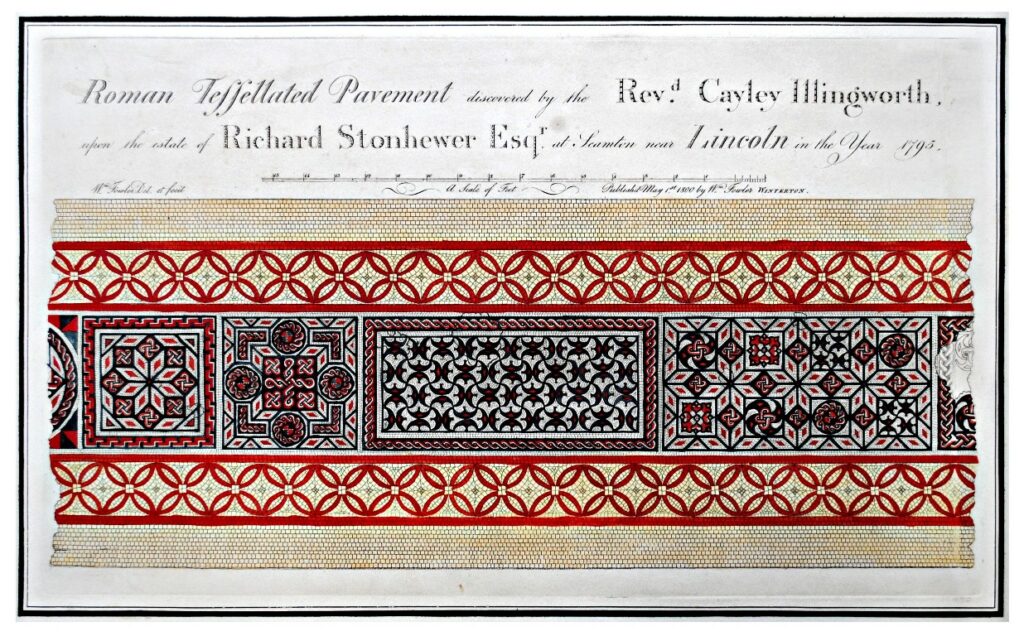

In 1747 Stovin wrote to the antiquary William Stukeley describing the discovery of a mosaic. This was the Winterton Ceres Mosaic, subject of William Fowler’s first drawing in 1796.

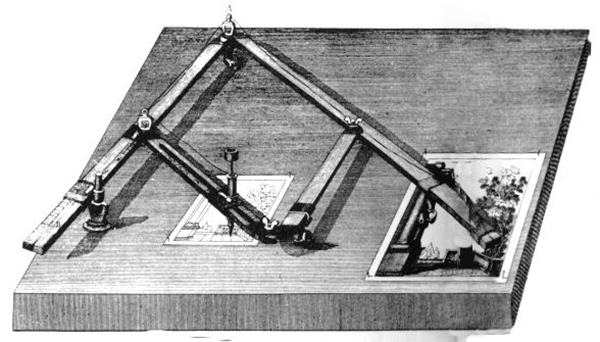

Encouraged by the interest shown in his drawing, William Fowler had copper-plate engravings made from it by his brother-in-law, John Hill of London. The resulting print was published in 1798. Admiral Shirley then asked William Fowler to create an engraving of the Horkstow Mosaic. His second career as a publisher of prints had begun.

Watching the Horkstow Mosaic plates being made convinced William Fowler he could do it himself. From then on, he etched all his copper-plates at Winterton. The resulting prints were hand-coloured by William Fowler, his sister Ann, his children and apprentices in their spare time. As well as Roman mosaics, Fowler drew and published engravings of Medieval tiled floors, stained glass, church architecture and fittings such as fonts.

William Fowler worked hard building his business, following his antiquarian interests in his spare time. One of his employees recalled how he would often work 18 hours a day. In 1804 William Fowler published the first of three series of engravings. The work was highly acclaimed. As Sir Joseph Banks said “Others have shown us what they thought these remains ought to have been, but Fowler has shown us what they are”.

In many cases Fowler’s engravings form an important record of items that have since been lost. For example, the Scampton Mosaic had a shed built over it for protection, but the next landowner used this as a cattle shed. The animals trod all over the mosaic and destroyed it.

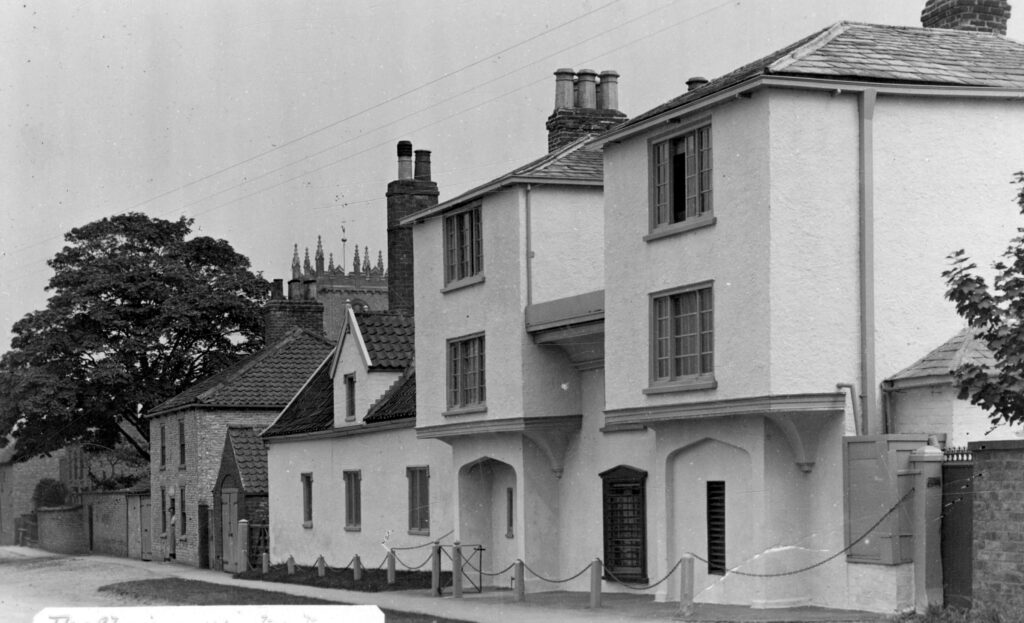

William Fowler’s House ‘The Chains’, West Street in Winterton

William Fowler lived for much of his life at 53 West Street in Winterton, which he converted from two cottages into a large house in around 1800. He designed it in a mixture of Gothic revival and Tudor styles.

The two large upper storey bays projecting over the front, combined with rendering gave it a striking appearance that is virtually unchanged today. William Fowler called it “Parva Domus”, but it became known as “The Chains” from a low chain fence which stood in front of the house.

The house was constructed in a mixture of brick and limestone to an ‘L’ shaped plan, with William Fowler’s workshop in the south facing wing. It was here that he and his workmen made the carvings, doorframes and windows for his buildings, as well as individual pieces of furniture.

Between 1827 and 1828, Fowler converted a barn at the rear into the “Gothic cottage”, where he spent his remaining years with his brother, James Fowler’s widow, acting as his housekeeper.