Saints and Sinners: Medieval Ritual and Religion

Rose Nicholson, Heritage Manager

Welcome to Saints and Sinners, an on-line exhibition exploring ritual and religion in North Lincolnshire during the Medieval period.

Introduction

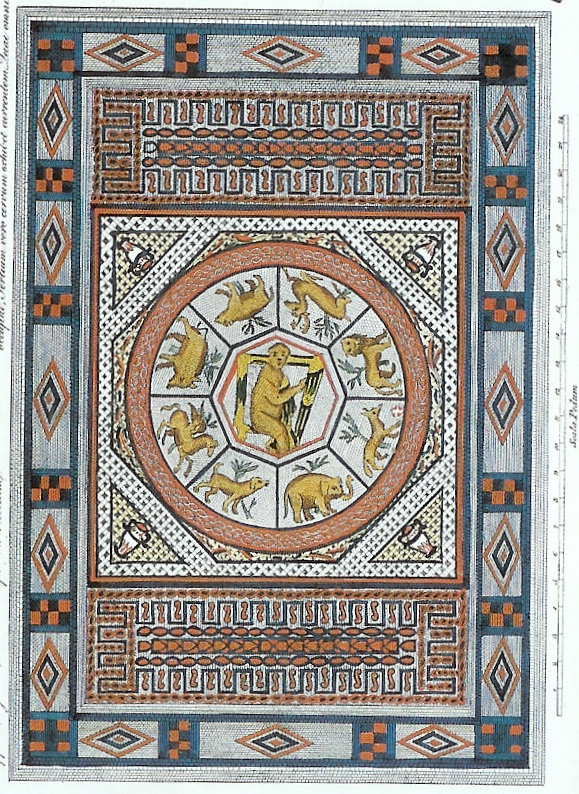

The Roman period saw many gods and goddesses worshipped in Britain. Alongside native Celtic gods, the Romans introduced deities from all over their empire. As well as Classical gods such as Mars, Jupiter and Venus, there were Eastern cults like that of the Asiatic goddess Cybele. Christianity was one such Eastern cult introduced to Britain during the Late Roman period. In AD 380 Christianity became the empires official religion.

We don’t know how far Romano-Britons had adopted the new Christian religion by AD 400.Evidence suggests the progress of Conversion was slow. Christianity was concentrated in towns, among army officers and administrators and the landholding elite.The Christian Church in Roman Britain may have been relatively small scale and low-key. Though few Romano-British buildings can be safely identified as churches, one is known at Lincoln. The church of St Paul in the Bail in Lincoln’s Roman forum began in the late fourth century as a timber structure with an apsidal end. It was rebuilt in the fifth century and demolished in the sixth century.

As the Western Roman Empire collapsed during the fourth and fifth centuries, pagan Anglo-Saxons arrived in England. The people they found living in North Lincolnshire were a mix of pagans and Christians. The arrival of the Anglo-Saxons saw Christianity retreat to Britain’s Celtic fringes – Cornwall, Wales, the Isle of Man, Ireland and Scotland. Paganism was again on the rise.

When the Anglo-Saxons arrived in England, people were on the move throughout Europe. With the Western Roman Empire under attack the Romans invited Germanic mercenaries to settle in Britannia. At the same times changes in sea level caused flooding in the northern European Anglo-Saxon lands, forcing them to look for new territories across the North Sea.

Early Anglo-Saxon Pagans

The Early Anglo-Saxon migrants were pagans. Anglo-Saxon paganism had developed from northern European Iron Age pagan religions. It had a hierarchy of divine powers. At the top were gods and goddesses. These included Tiu, god of war and the sky, Odin, chief of the gods, his son Thor the thunder god, and Freya, Odin’s wife and goddess of the home. Their names survive in our words Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.

Below the gods were beings like elves, spirits and ghosts. Central to belief was the desire to gain divine approbation or good luck. Whereas Christian’s believed people were free to choose their own path, Anglo-Saxon pagans saw life’s path as in the hands of fate. Worship included votive deposits, monumental mounds and natural phenomenon such as thunderstorms. It took place at natural features such as groves, marshes, wells and springs.

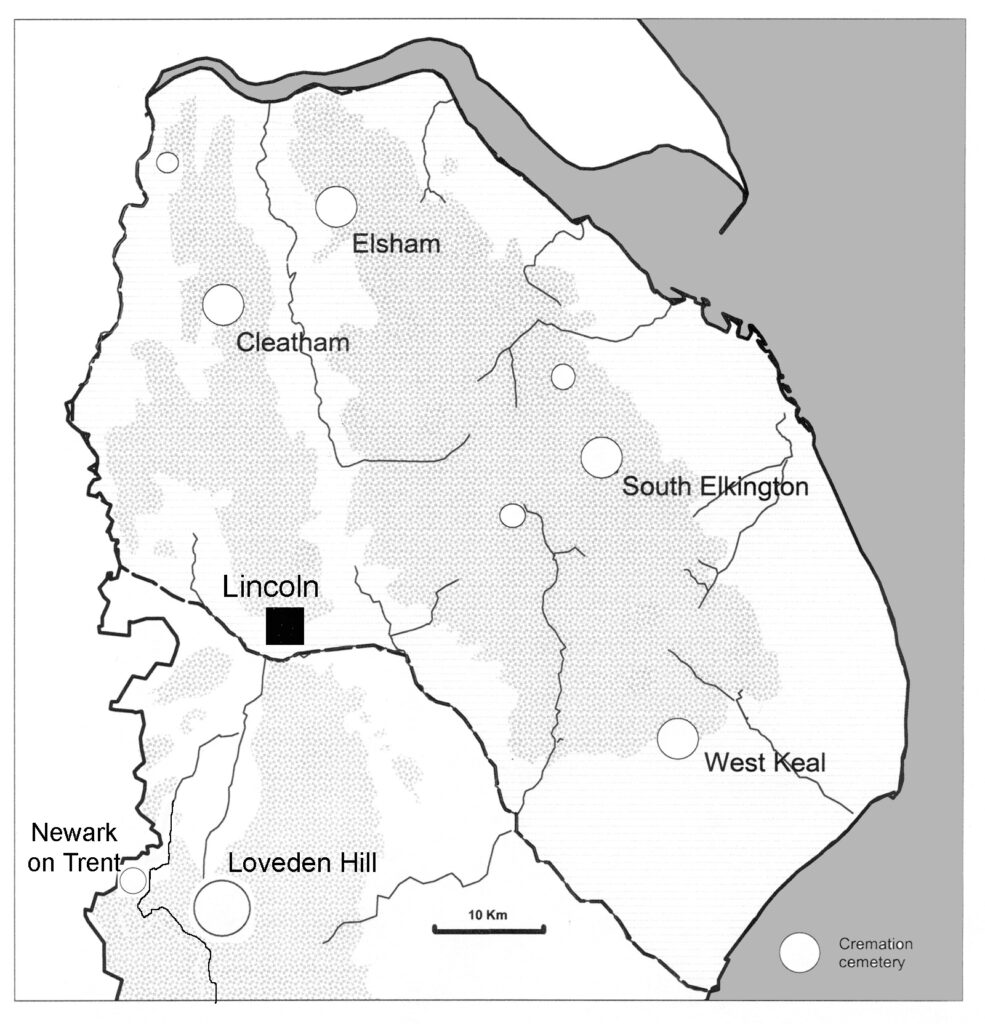

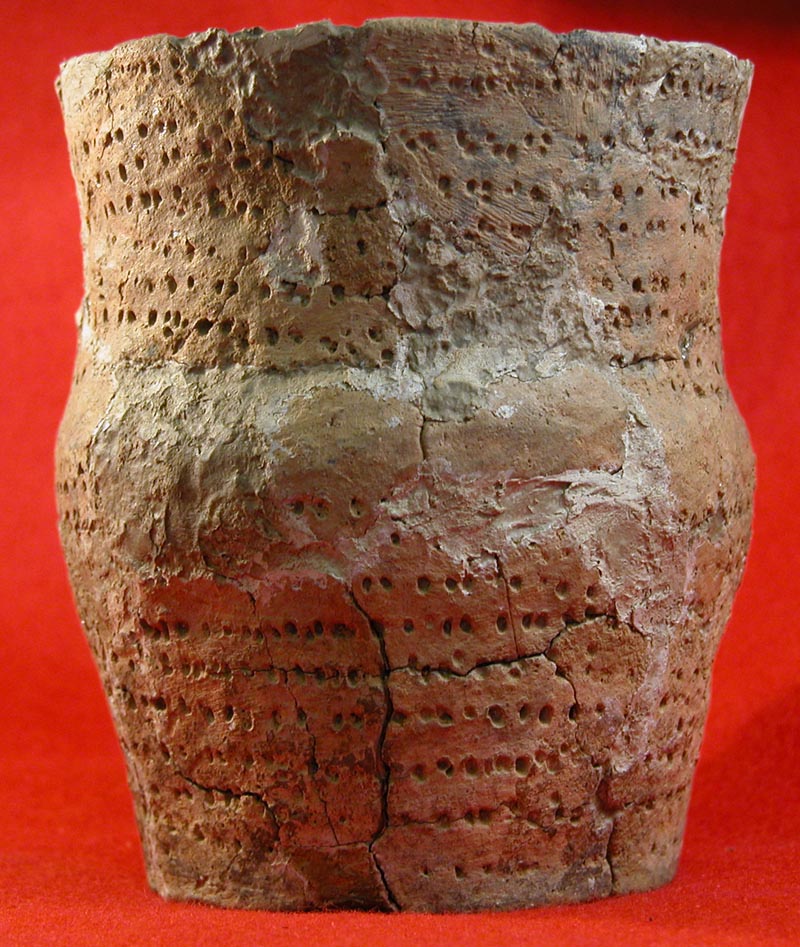

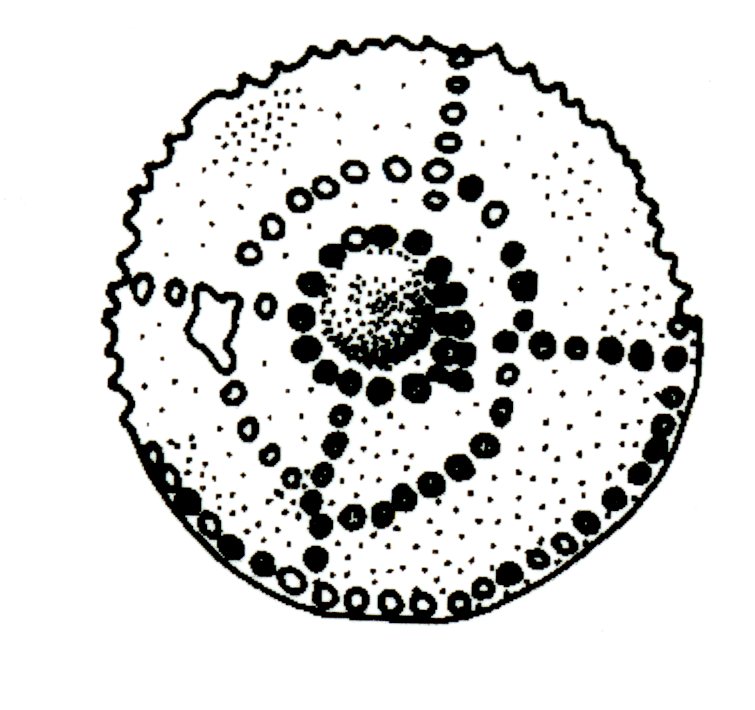

Much of what we know of the Early Anglo-Saxons comes from their cemeteries. Within these cemeteries there is much evidence for ritual behaviour. Their dead were usually buried in cemeteries, either as cremations or inhumations, along with suites of grave goods. Within a cemetery there was not much social differentiation.

The Anglo-Saxon Conversion

The Anglo-Saxon conversion took place during the seventh century and was largely complete by the 730s. Christianity was reintroduced to England from both Rome and the isolated Celtic fringes of Britain.

Conversion brought great changes to English society. Pagan rituals brought benefits to an individual or community. Paganism was embedded in many aspects of life, such as warfare, storytelling, the agricultural calendar and medicine. Priests were powerful and as kingly power developed there may have been tension between priests and kings. Conversion gave kings power over religious affairs. Christian clergy were under the king’s protection and operated at sites chosen by the king. By providing counsel to quarreling rulers, the Church promoted peace and played a major role in unifying the English people.

Perhaps influenced by Christianity, the seventh century saw changes in how people buried their dead. Cemeteries tended to be closer to where people lived. There are no cremations, only inhumations in the ‘Final Phase’ cemeteries such as Sawcliffe, Cleatham and Castledyke. Graves were aligned west-east and laid in rows. Many graves have no objects. When grave goods are included, they are mainly knives, small dress fittings or small personal objects, and some cross form objects with Christian significance.

Despite the conversion, stories of the pagan gods continued to be told and represented. Some objects combine Christian and pagan imagery. The Franks Casket has scenes from the pagan story of Wayland the Smith-god alongside the Christian Adoration of the Magi.

Anglo-Saxon Monasteries

Anglo-Saxon monasteries were communities of men or women dedicated to a life of prayer. Royal families often granted monasteries huge estates, along with great power and influence.

Often Anglo-Saxon monasteries were founded on island or peninsular sites. A monastery consisted of chapels, churches, cells and buildings scattered across a landscape. The isolated locations represented the separation of the spiritual life from the sinful world. This was the key belief of monasticism.

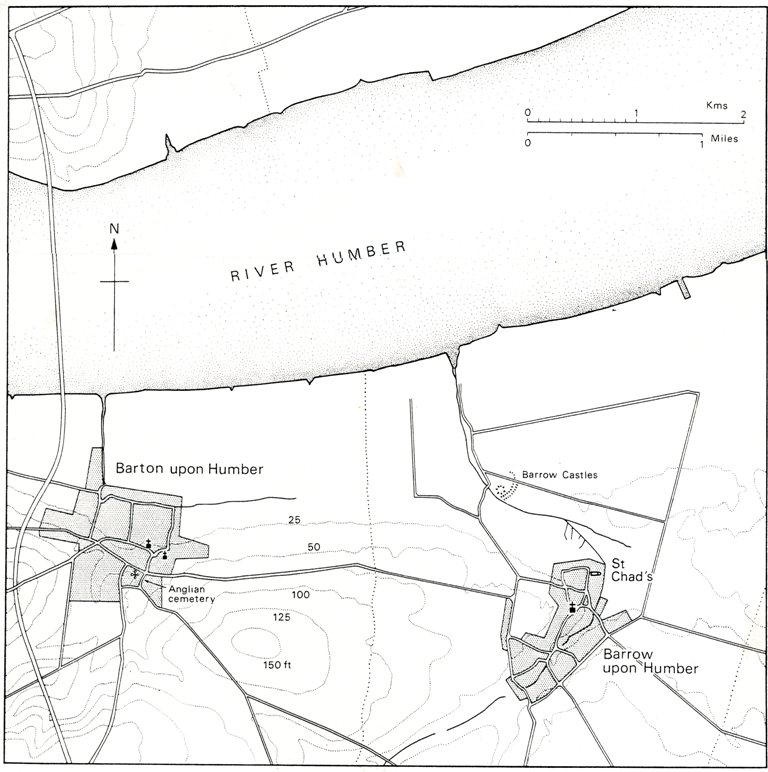

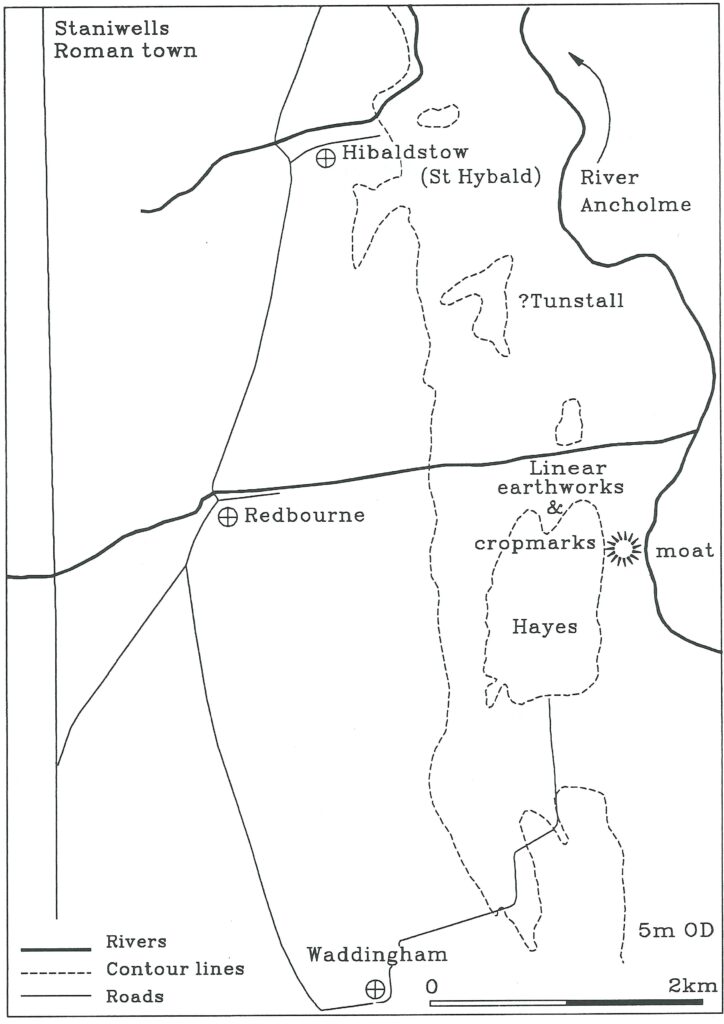

Monasteries were founded in North Lincolnshire from the mid seventh century. This was after the Conversion of Lindsey to Roman style Christianity. Chad founded a monastery at Barrow-upon-Humber on an estate granted by King Wulfhere of Mercia. Hygbald was abbot at a monastery in the vicinity of Hibaldstow. References to a monastery founded by St Aethelthryth of Ely are thought to refer to West Halton, where the Medieval church was dedicated to the saint. Excavations at Flixborough may show a ninth century monastic phase to the settlement.

During the seventh and eighth centuries most monks and nuns were concerned with their own spiritual life within the monastery, rather than evangelical work in the community. The spiritual needs of the populace were served by travelling priests from the monasteries under the control of the bishops. The Church brought literacy back to England, missing since the departure of the Romans. In the monasteries monks worked as scribes, recording and copying manuscripts by hand. Books such as the Lindisfarne Gospels were elaborately painted and illuminated.

Viking raids on monasteries from the eighth century saw the Church decline. The pagan Danes set about conquering England until Alfred the Great halted their advance. Though the Vikings were converted by the end of the ninth century, monasteries didn’t reappear in North Lincolnshire until the eleventh century.

Late Saxon Burials

By the ninth century most people buried their dead in Christian cemeteries associated with minsters, parish churches and chapels. However not all burials were at or near to churches. Isolated burials have been found at Barrow-upon-Humber and some Late Saxon cemeteries have no evidence for a church. A number of churches and their cemeteries appear to go out of use during the Late Saxon.

During the tenth century burial in your parish churchyard for a fee became obligatory. Churchmen enclosed churchyards as they now had a financial interest in their burial grounds. Enclosure often resulted in the area devoted to burials being reduced. This may explain occasional discoveries of Middle and Later Saxon burials immediately outside of churchyard boundaries, for example at Whitton.

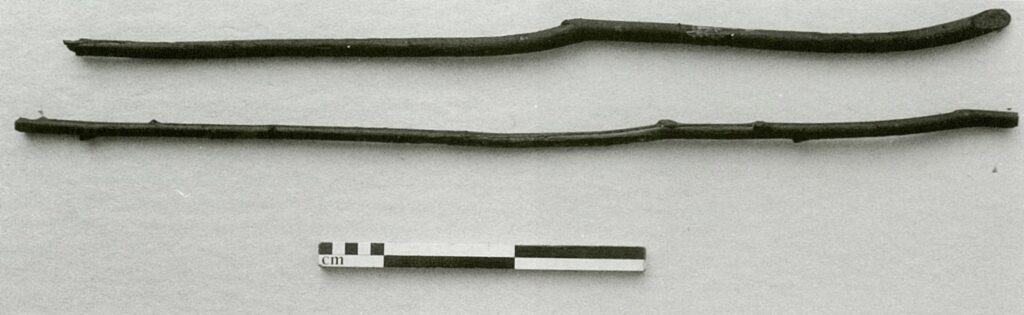

Burial was not as elaborate as it had been in earlier centuries. Funerals conveyed messages about the deceased’s status and the fate of their soul in the afterlife. Differing traditions and beliefs saw much local variation. This continued even as the Church tried to gain firmer control during the tenth and eleventh centuries. At St. Peter’s, Barton-upon-Humber the range of burials included wooden coffins, plank or stone-lined and plain earth graves. Some graves had been filled with lime or liquid mud. Others included charcoal deposits or hazel rods.

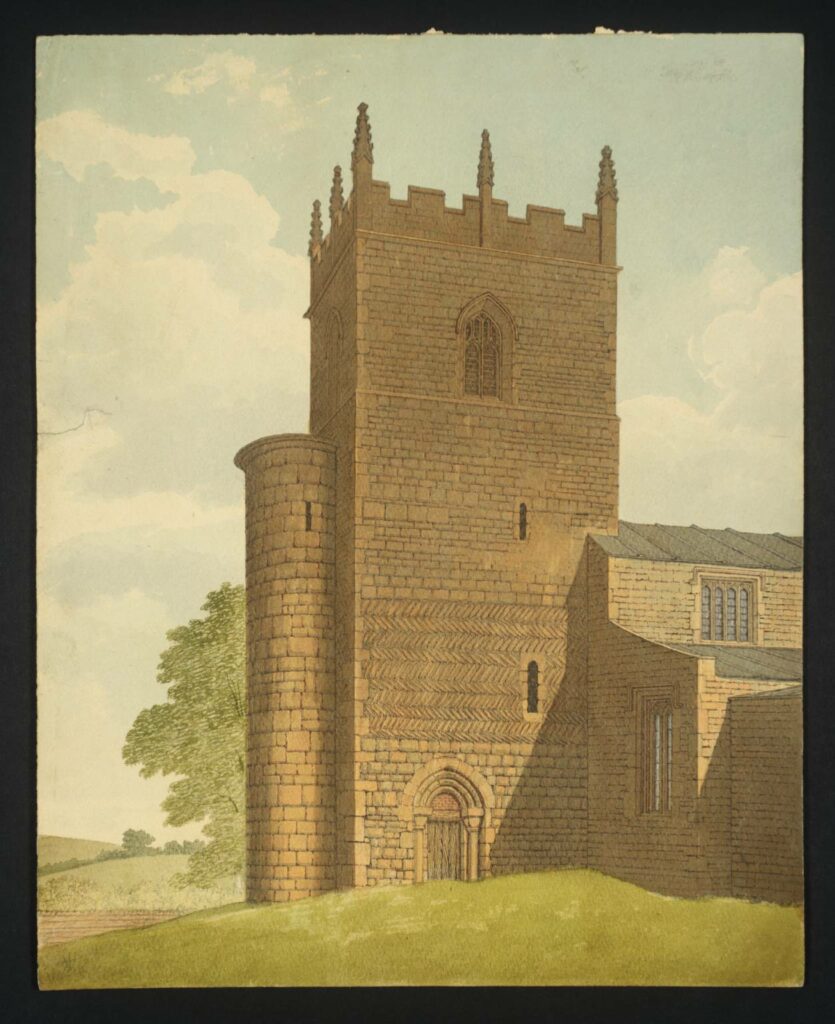

Broughton Church

St. Mary’s, Broughton has an eleventh century Saxon tower-nave. The tower was the private chapel of the local lord with the ground floor serving as the nave. A small chancel stood where the Medieval church now stands. The tower is very visible in the landscape. It may have been a marker for the moot meeting place of the Manley wapentake and a muster-point for the lord’s forces.

The tower was built mainly from local stone, as well as some re-used Roman masonry. Distinct bands of masonry are visible in the towers construction, including a band of herringbone masonry. The rare external stair-turret includes blocks of Roman Millstone Grit. The Saxons re-used Roman masonry to make a deliberate statement of connection with their Roman predecessors.

Anglo-Norman Lincolnshire Towers

Lincolnshire Towers are a group of 60 church towers unique to Lincolnshire. The Towers were built after the 1066 Norman Conquest in the late eleventh century.

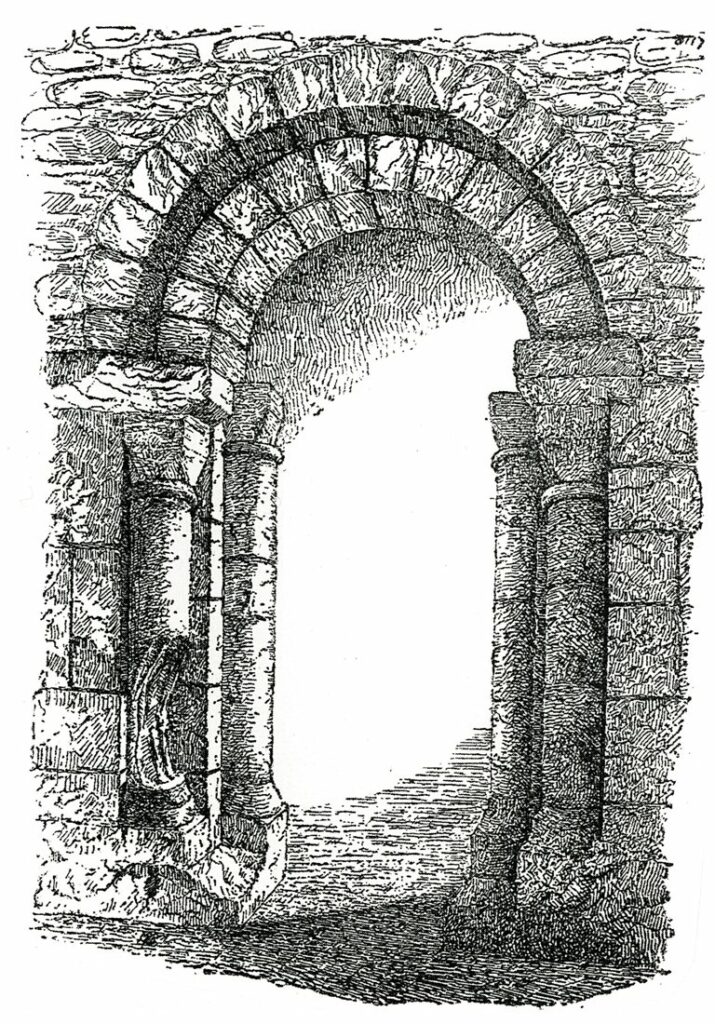

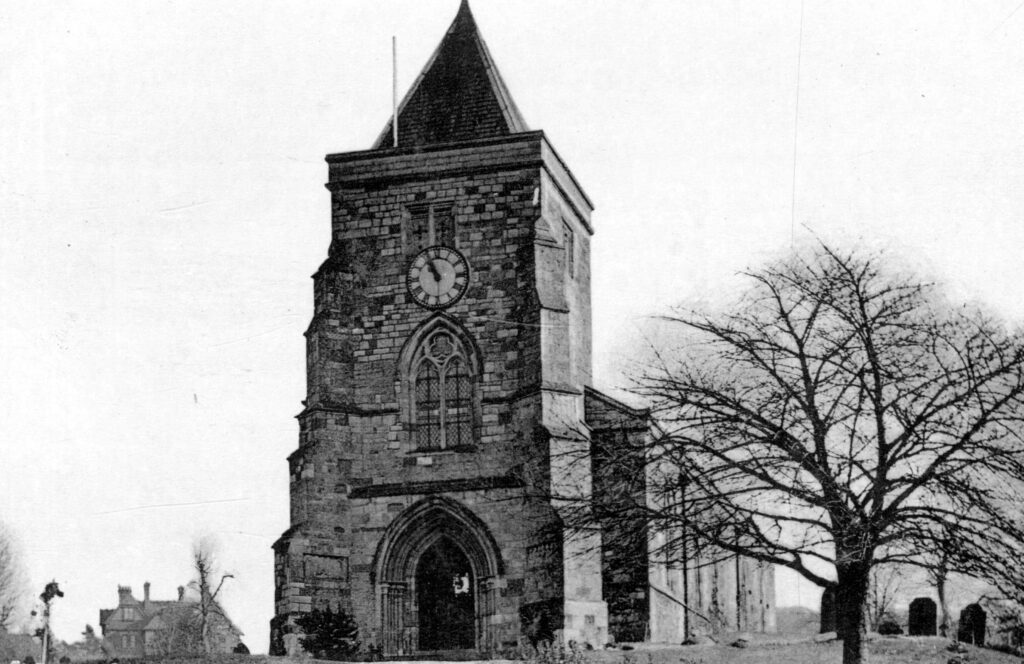

All the towers are in Early Romanesque style. They have a square plan and a number of unequal storeys. On the tower exterior, a line of decorative stonework separates the storeys . The upper bell chamber on the top floor usually has large ornamental windows. Other typical features include a simple west doorway on the ground floor, an undecorated tower arch on the east wall leading to the nave and small windows on the first floor.

The west end of existing churches had Lincolnshire Towers added as bell towers. This was due to a new funeral service introduced to the Lincoln Diocese by the Normans. The day before a funeral saw the coffin brought to the tower for an overnight vigil. During the funeral the west door was opened and the coffin moved into the graveyard whilst the bell was tolled. Bell ringers watched through the first floor windows overlooking the graveyard so the bell could be tolled during the funeral.

Medieval Religion

The Church played an important part in everyday life. Almost everyone believed in God, Heaven, Hell and Purgatory where souls dwelled until they were pure enough to enter Heaven. People prayed for themselves and their friends and relatives souls. They could even pay for pardons to ease passage through the afterlife.

The Medieval Church was Catholic, though people incorporated aspects of pagan religions within it. The Church took over sacred pagan shrines. It also adopted the use of clerical costume, altars, incense, music, veils, cloths, decorative foliage, seasonal festivals and the making of sacred fires. The general population also incorporated things the official Church didn’t. It was commonplace for people to use prophecy, amulets and charms as protective magic. Local wise women also used cunning craft. At the heart of Catholicism was a belief in the power of rituals and saints relics, which were much like the spells and potions sold by local cunning folk. Churches had patron saints and the help of saints was regularly sought. Midwives urged pregnant women to call on the Virgin Mary to reduce the pain of labour.

Church leaders often expressed concern about the prevalence of pagan practices amongst Catholics. An eleventh century decree ordered priests to ‘entirely extinguish every heathen practice; and forbid worship of wells, and necromancy, and auguries and incantations, and worship of trees and worship of stones, and that devil’s craft which is performed when children are drawn through the earth’.

Doom paintings of the Last Judgement when Christ sent souls to Heaven or Hell were often painted on the walls of churches. They served as a potent reminder to parishioners to avoid sinning if they wished to go to Heaven rather than the agonies of Hell.

Medieval Parish Churches

After the Norman Conquest most of the few Late Saxon churches in North Lincolnshire were rebuilt. Some retained Saxon structural elements. Others have pieces of stonework re-used in later rebuilding or free-standing in the church or churchyard. The tenth and eleventh century church building boom resulted from the creation of parishes. Parish churches were able to keep some of the tithe paid by the locals to the minster church. Landowners paid for the erection of the church and endowed it with land for its maintenance and a house for the priest.

Parish churches were built for worship and their architecture embodied Christ on earth.

The spire points to heaven and the carvings around the entrance point to the holiness of the building. Inside the aisle and pews represent a ships gangway carrying worshippers to God at the altar. The interiors were full of symbolism and devotional aids, designed to contribute to the mystery of the sacrament. Wealthy parishioners demonstrated their piety by paying for private chapels, chantries, tombs, stained glass windows and monuments within parish churches.

The parish church was at the centre of a community. The parish priest was closely involved in his parishioner’s lives, from baptism to marriage, and the funeral after death. New mothers were purified by ‘churching’ after birth. In many places the churchyard was used as an open-air meeting place, for festivals, feast days and markets.

Medieval Monasteries

Anglo-Saxon monastic foundations disappear with the arrival of the Vikings. Crowland Abbey was the only Lincolnshire monastery left at the Norman Conquest. The years following the Conquest saw a monastic revival. Medieval monasteries became some of England’s wealthiest landowners. Benefactors gifted land and property in return for daily masses for their souls. Monasteries were the centres of farming estates, places of learning and hospitals.

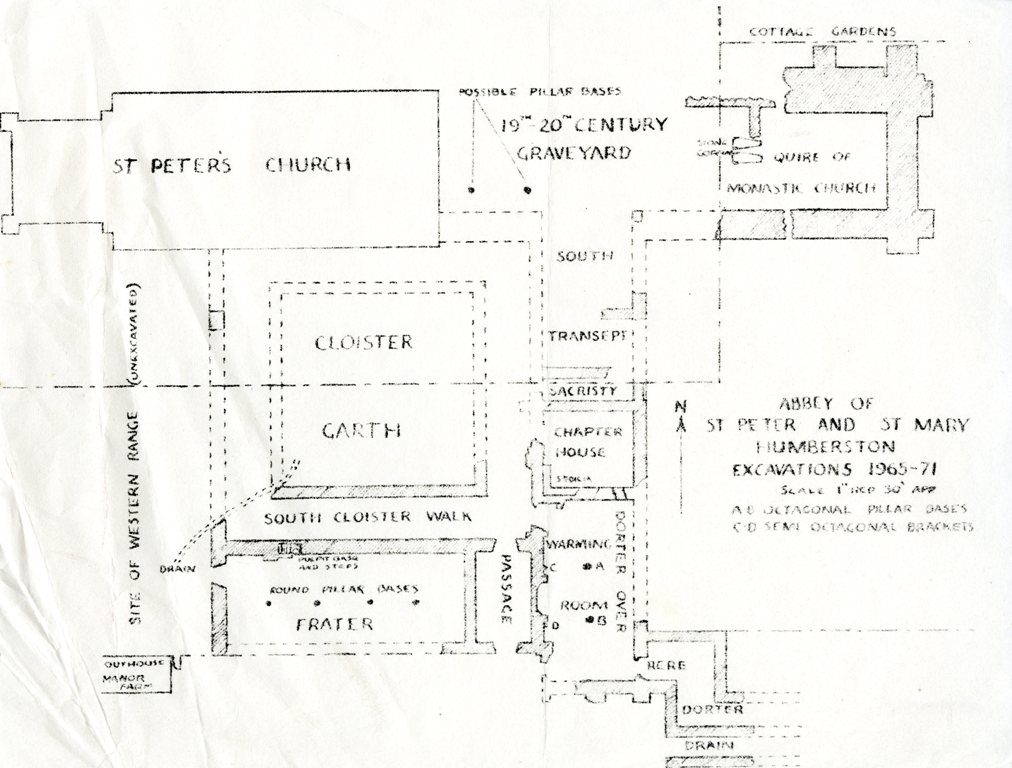

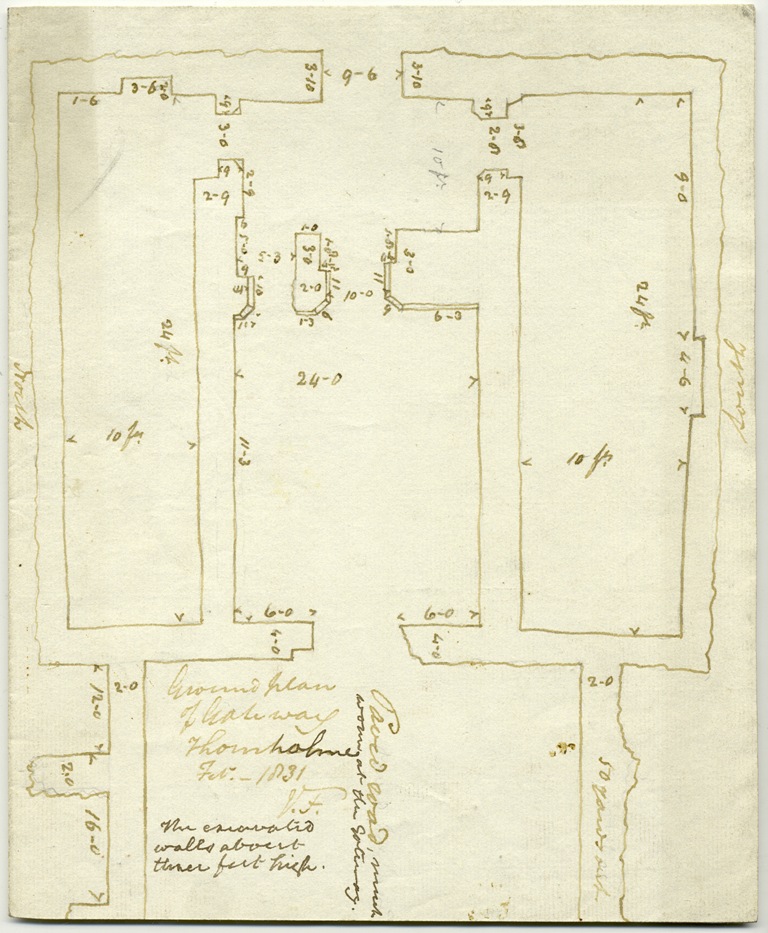

Monasteries belonged to different religious orders. Thornholme and Elsham Priories were Augustinian. Alkborough Priory was Benedictine. Redbourne’s St Mary’s Priory was a Gilbertine double house with both monks and nuns.

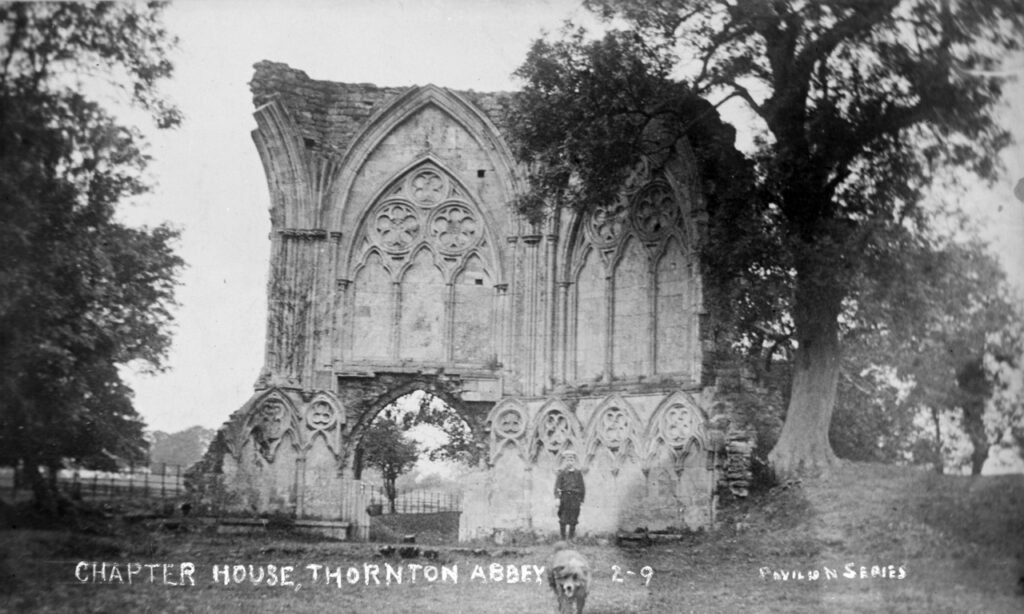

Most monasteries were small with just a few monks or nuns. Belton’s Augustinian Hirst Priory supported one canon with two servants. Elsham Priory supported eight canons and a prior. Thornton Abbey was a larger community with 30 canons, a prior and a number of lay brothers.

Daily life for a monk depended on their religious order. There were some similarities. Much time was given over to prayer, with eight daily church services starting at 2am. When not praying monks carried out tasks linked to the running of the monastery. They were helped by servants and lay brothers. Lay brothers were men who had made religious vows, lived in the monastery and carried out manual labour.

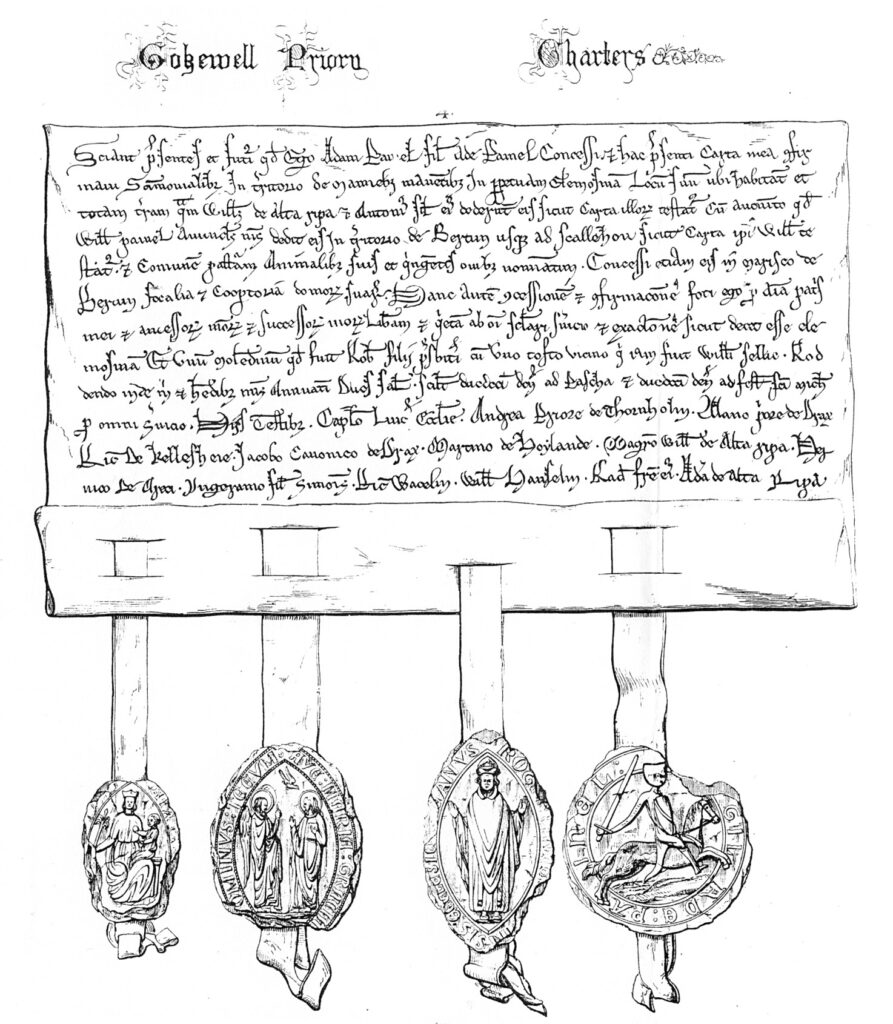

Thornton Abbey was founded in 1139 by William le Gross, Count of Aumale, and Lord of Holderness as a house of the Canons Regular of St. Augustine. It was one of the Order’s richest monasteries, with an annual income of £591.0s.2¾d on its dissolution in 1539.

Thornton Abbey was one of only a handful of England’s greatest abbeys to survive Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. The ‘Thornton Chronicle’ is a history compiled in 1532 based on earlier documents. We gain fascinating insights into the early life of the Abbey through the extraordinary survival of this book. The original book is now held in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Medieval Pilgrimage

Saints are people thought to have a special holiness or closeness to God. Anglo-Saxon saints included important Biblical figures. These included Peter and Paul, and Christian martyrs killed during the Roman persecutions. People recognised important Anglo-Saxon figures as saints. The founders of religious houses and those who died in battle against pagan kings all became saints. Many more were declared saints during the Medieval period, including historical figures like Archbishop Thomas Becket. Saints lives were used as examples of Christian virtues like faith and charity. Different saints became famous for their abilities to protect people, animals and property from misfortune. They could also cure illnesses and bring good luck.

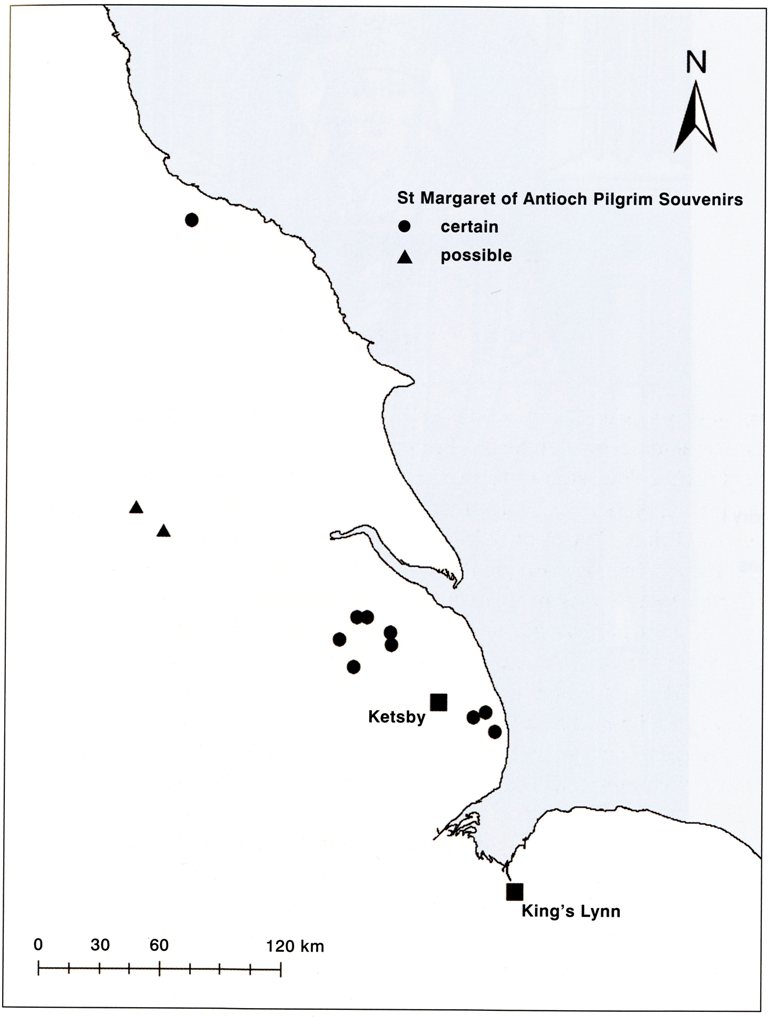

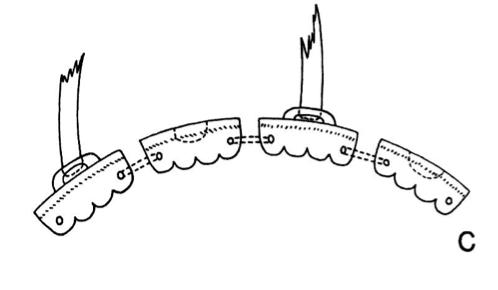

Relics were made from the body parts or possessions of saints and sites connected with them developed as holy shrines. The Medieval Church encouraged people to go on pilgrimage to shrines. Important shrines included that of Thomas Becket at Canterbury and the Virgin Mary at Walsingham.

Pilgrims purchased mementos from the shrines they visited. Pilgrim badges had symbols identifying the saint and shrine. Saints were thought close to God. Their relics held mystical powers that could be transferred to souvenirs by touch. Souvenirs became magical touch-relics that could cure diseases. Pilgrims also collected small bottles or ampullae filled with holy water. Once home, the ampulla was hung up in a house for good luck. Or the holy water was sprinkled on fields for fertility. Both acts demonstrate a continuance of pagan beliefs dressed up as a Christian rite.

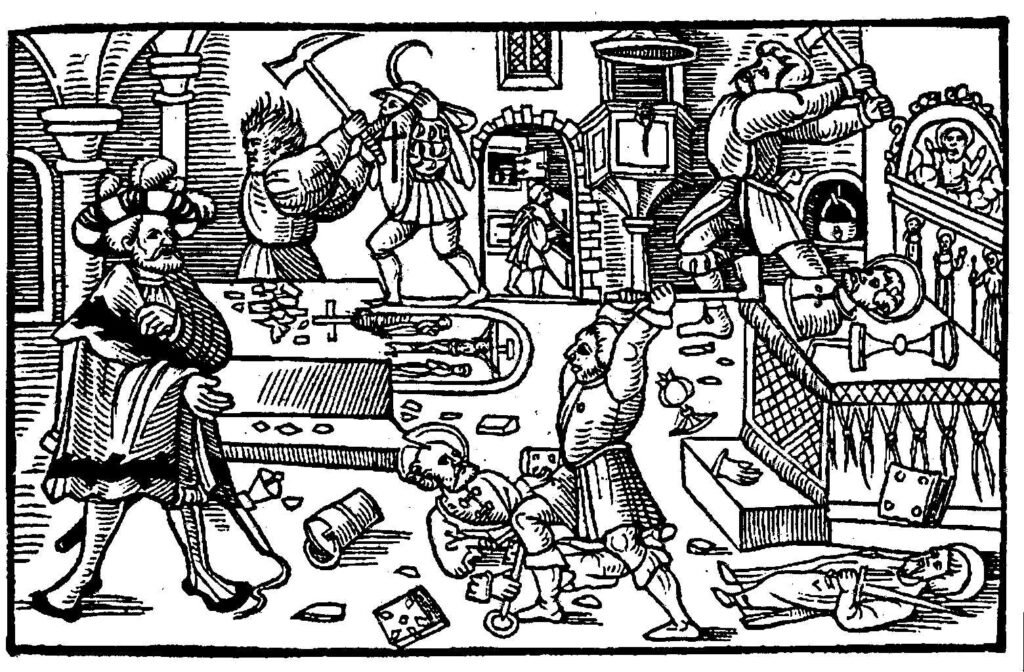

Medieval pilgrims were like modern day tourists. They brought wealth and investment to the communities that housed shrines. Pilgrimage was undertaken for religious reasons. It was also a way to escape everyday life, meet new people and swap stories. The tradition came to an end in 1538 when Henry VIII banned pilgrimages as part of sweeping moves against the Church. Relics could no longer be displayed for worship and shrines were destroyed.

The Reformation

The Medieval Church was powerful. Kings believed themselves to rule by Divine Right. As the Church saw the Pope as Christ’s premier representative on earth, this often led to the state and Church clashing. By the sixteenth century critics thought the Church was spiritually bankrupt. Its officials were said to be corrupt and more concerned with their own wealth than the well-being of their parishioners.

Matters came to a head in the mid-sixteenth century when Henry VIII’s Reformation saw the English Church split from Rome. The primacy of the Protestant English Church over Rome’s Catholic Church was established. Monasteries were dissolved, their income seized, their assets sold and their monks and nuns retired. Though monasteries were said to be immoral and corrupt, dissolution certainly benefited the Crown, providing much needed income.

The Lincolnshire Rising was a short-lived popular rebellion that took place during October 1536. It was a prelude to the much larger Pilgrimage of Grace. The Lincolnshire Rising began in response to unpopular policies, such as the Dissolution of the Monasteries and the suppression of Catholicism. When the rebels reached Lincoln they were told Henry VIII would listen to their demands if they dispersed. However he had given orders for the army to kill the rebels. The rising was quickly suppressed and 47 people executed.

Witch hunting in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries usually happened in places that had experienced significant changes in religious practices and beliefs as a result of the Reformation. It is thought witchcraft filled the void created by the suppression of Catholicism.