Dead and Buried: The Archaeology of Death and Burial

Rose Nicholson, Heritage Manager

Introduction

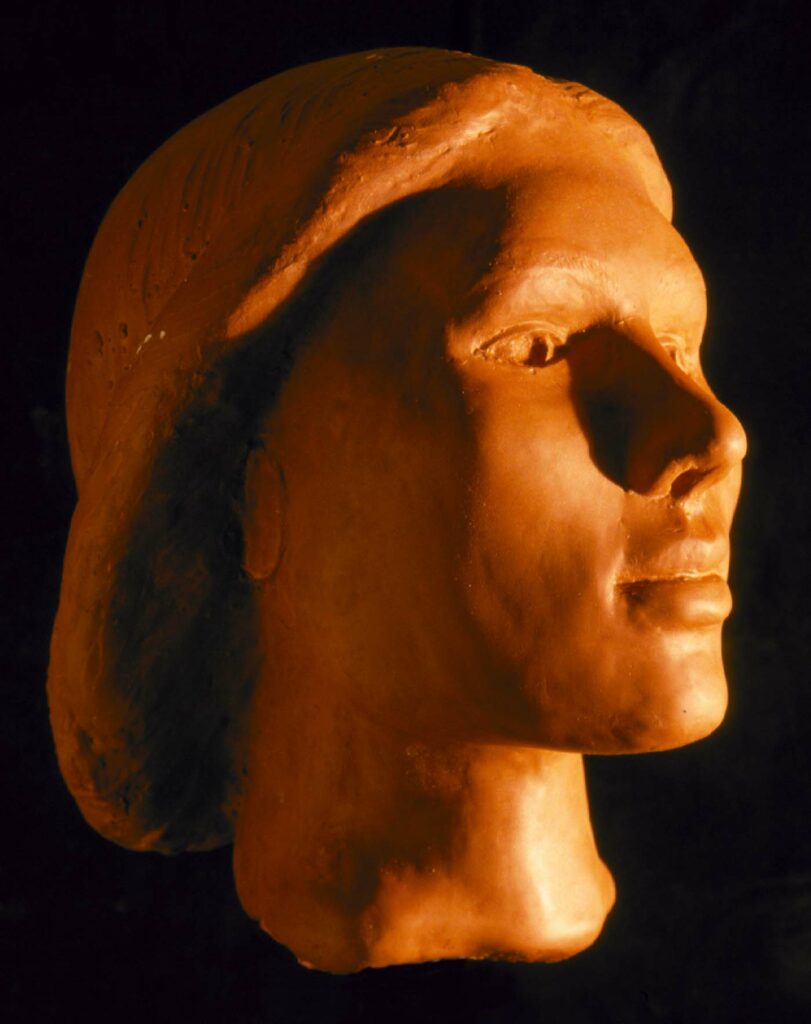

This online exhibition looks at how burial practices in North Lincolnshire changed between the Prehistoric and Medieval periods. Human skeletal remains are regularly found during archaeological excavations and building works. The study of these remains can tell us a lot about a person, from information such as their lifespan, sex, and appearance, to the area where they grew up and any illnesses they suffered from.

By studying human remains we can also learn about past attitudes to death and the afterlife, as well as social organisation and how people lived.

The Neolithic

During the Neolithic period, the development of agriculture led to one of the biggest changes in human history. People began to move away from a roaming hunter-gatherer existence to a more settled farming lifestyle.

As settlements were established and the population increased, people built the first large tombs and monuments to mark land ownership or for spiritual reasons. These included barrows, communal burial places that could contain the remains of up to fifty people. They were reopened from time to time to add new remains or remove parts of the older ones for ritual practices.

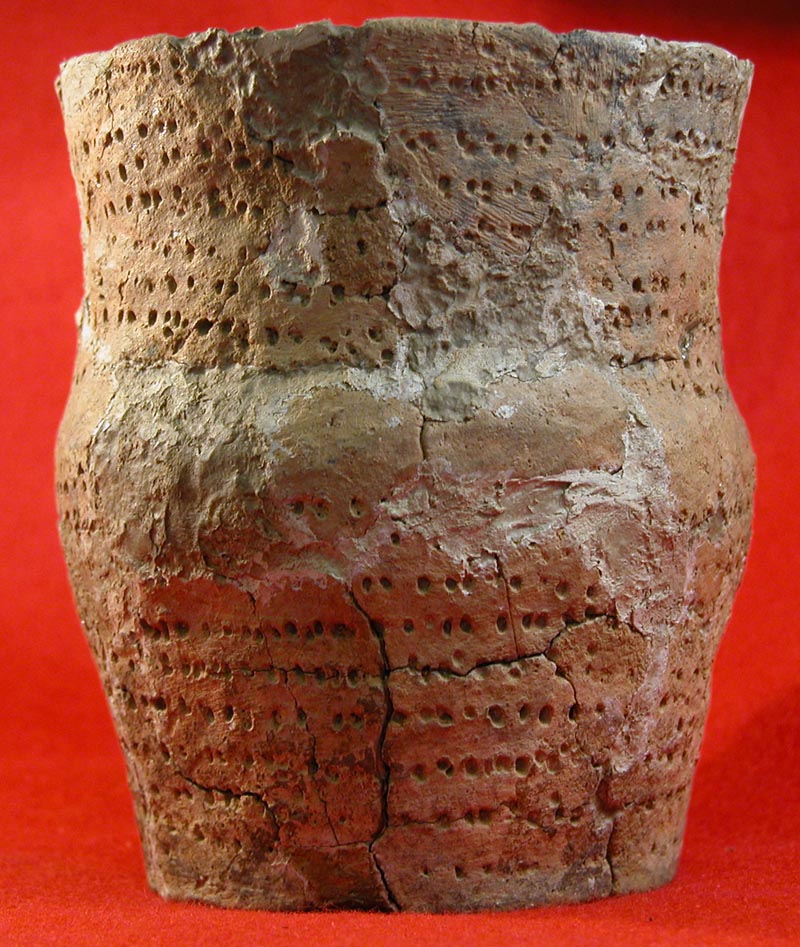

The Later Neolithic saw the arrival of the Beaker people from Europe, bringing a new practice in which bodies were buried in individual graves.

Bronze Age

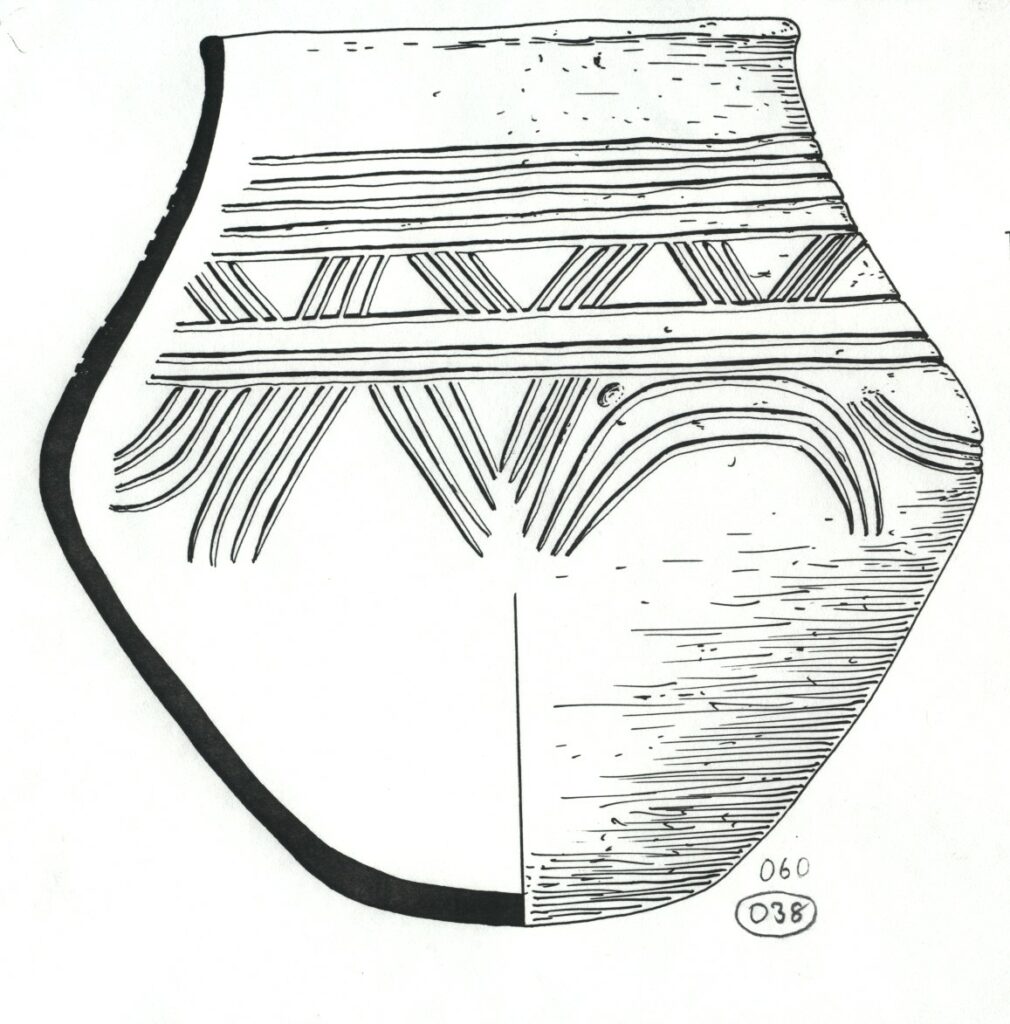

During the Early Bronze Age the dead were often buried in a crouched position accompanied by a pot. By the Middle Bronze Age it was more common to cremate the bodies and place the ashes in an urn.

Both burials and cremations were usually buried beneath circular mounds or round barrows. These barrows were prominent features in the landscape and were used as focal points for the community. They were once common in North Lincolnshire, but most have unfortunately now been ploughed flat, with only their ditches surviving.

Iron Age

There are a marked absence of human remains from the Early Iron Age. A few burials are known, but these only account for a tiny proportion of the population. This is thought to be down to a range of practices such as exposing the dead to the elements and digging up existing burials to remove certain bones.

By the Late Iron Age burials are once again seen in the archaeological record. They are often found in places such as disused storage pits and field ditches. A small burial ground found at South Ferriby, dated to 370-100BC, contained bodies found in a typical tightly crouched position.

Roman

The Romans brought new burial rites to Britain, although native practices continued alongside them.

Under Roman law it was forbidden to bury bodies within the boundaries of a settlement, although a cluster of graves found in a small 2nd century settlement at Hibaldstow suggests that this law wasn’t always obeyed.

Bodies in the Early Roman period were usually cremated and buried under mounds, in disused pits and ditches or in cemeteries. By the Late Roman period burials in large cemeteries was common and personal items such as jewellery were used as grave goods.

Coffins were popular by the 2nd century. Poorer people were buried in wooden coffins with metal fittings, while the more well-off used coffins of stone or lead.

Anglo-Saxon

Saxon settlers introduced new burial rites which were adopted by the locals. Early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries were either mainly cremation or mainly inhumation, with inhumation becoming most popular by the 6th century. Many of these cemeteries were associated with prehistoric monuments.

Most graves were accompanied by grave goods, although men were buried with significantly fewer items than their female counterparts.

By the Middle Saxon period burials were changing, a reflection of the conversion of pagan Saxons to Christianity. These new burials were aligned west-east in cemeteries and had few or no grave goods.

Late Saxon burials were largely Christian. By the 9th century most people were buried in cemeteries associated with churches and chapels, and by the 10th century it was compulsory to be buried in the local churchyard for a fee.

Medieval

Most Medieval burials followed the Christian practice of east-west alignment and no grave goods. Most people were buried in their parish churchyard, with different areas for people of different social status. Wealthier people were buried on the sunny south side of the church near the door, while poor people were buried on the darker north side.

High status people could also ask to be buried in a monastic cemetery. This was highly desirable as the monks would say prayers for the dead person’s soul. From the 12th century people believed in Purgatory, where the dead experienced suffering to purge them of their sins. Prayers could help to ease this suffering.